In my new book I have a section about ruff collars—those accordion-like, cartwheel-shaped gizmos that were in style from about 1530 to 1630. That’s a long time to be in fashion, expecially considering how incredibly ungainly and impractical (not to say unattractive) these things were. The Dutch wore them for even longer—they seemed to prefer being intentionally out of style. Even working people wore them, although theirs tended to be a much smaller version–because they had to work for a living.

In my new book I have a section about ruff collars—those accordion-like, cartwheel-shaped gizmos that were in style from about 1530 to 1630. That’s a long time to be in fashion, expecially considering how incredibly ungainly and impractical (not to say unattractive) these things were. The Dutch wore them for even longer—they seemed to prefer being intentionally out of style. Even working people wore them, although theirs tended to be a much smaller version–because they had to work for a living.

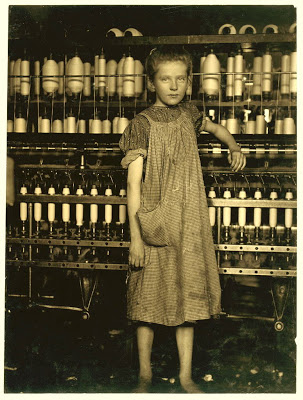

Making a ruff required huge skill and patience. The linen was pleated into folds in a figure eight pattern, using a “poking stick,” and creased with heated irons. By the 1560s, someone figured out how to make starch as a stiffener. Wheat was boiled to a goopy paste, spackled on, and brushed into every fold. The ruff was then dried in front of a fire, before the whole process was repeated. Then it had to be pinned onto a wire support (called an underpropper), which was in turn pinned to the neckline of the dress or other garment. This process could take hours. Even kids wore them.

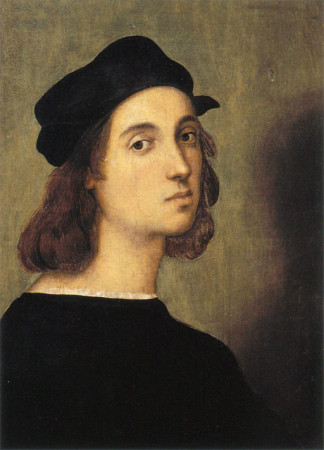

This is a boy. Lord Arundel. You can tell by the shoes.

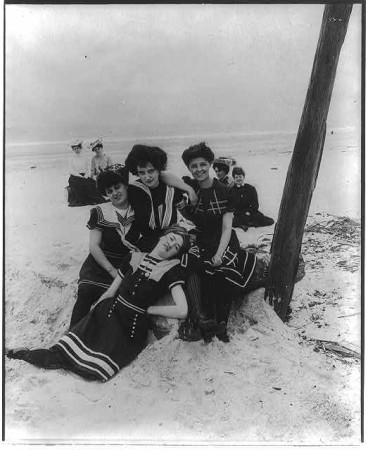

Ruffs were fragile. They drooped in wet weather. The bigger ones allowed the wearer virtually no freedom of movement. Members of the nobility wore huge ruffs to advertise their leisure status; the wearer was incapable of performing any physical labor. Spoons had to be made with longer handles to reach the person’s mouth.

Here’s Henry III of France. I’m pretty sure that’s a jewel, and not a botfly, on his head.

Just to see what it might have been like, I made a crude ruff out of cardboard and tried walking around with it. What a nightmare. You can’t see your feet—and I wasn’t wearing a floor-length farthingale. Here’s my husband, gamely modeling it for me. He’s a pretty good sport.

Sources: Liza Picard: Elizabeth’s London (125-6)

and Ewing, Dress and Undress (32)

![Monkshood or Wolfsbane David Baird [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sarahalbeebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Monks-hood_-_geograph.org_.uk_-_542573-450x325.jpg)

![cowbane By Anneli Salo (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sarahalbeebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/512px-Cicuta_virosa_Myrkkykeiso_IMG_0357_C-450x299.jpg)