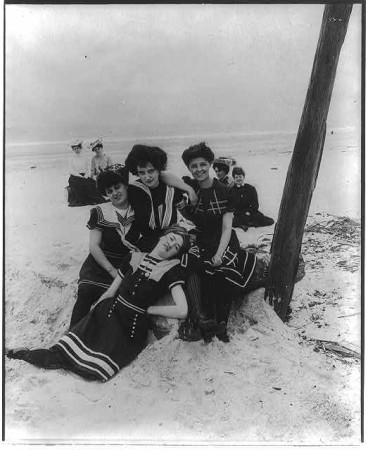

Mrs. Harvey W. Wiley, widow of the author of the Pure Food Act, displaying the shocking bathing costume of 1895 while Marjorie Gunnels wears the sensible one of 1936.

(Library of Congress)

I’m reading a book by the always-fascinating Steven Johnson, called How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World. His premise is that certain key innovations, such as the discovery of glass and refrigeration, set in motion a whole array of changes in society, and that they eventually triggered changes that you might never have predicted. The history of ideas observes a co-evolutionary process, he says, much the way that living things have co-evolved. He calls it the “hummingbird effect:” the evolution of pollen led to the symbiotic alteration of the hummingbird’s wing, which enabled it to hover alongside a flower. The co-evolution of ideas, he suggests, can work the same way.

Being me, I turned straight to the chapter about sanitation (entitled “Clean”). He posits a fascinating theory: the adoption of widespread chlorination of drinking water led to a rapid co-evolution in women’s bathing suit fashions. The story in a nutshell—in the early twentieth century, a New Jersey doctor named John Leal took a huge risk. He unilaterally made the decision to add calcium hypochlorite, aka chlorine, to the public drinking water supply in New Jersey, in an effort to kill disease-causing bacteria. His theory was that although chlorine is a deadly poison in large doses, it could be extremely beneficial in smaller ones, but no one had ever tried to chlorinate drinking water before. His bold experiment worked, and epidemics of typhoid and dysentery, terrible killers especially of young children, dropped precipitously.

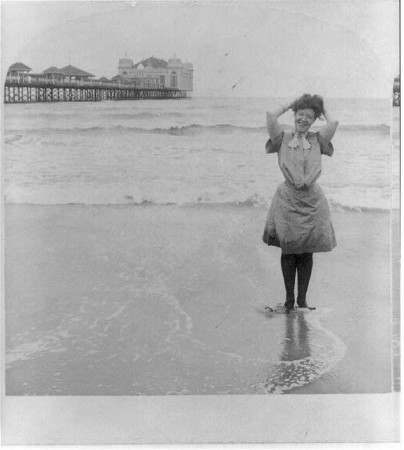

But another change co-evolved: After World War I, ten thousand chlorinated public baths and pools opened up across America, which, Johnson asserts, resulted in rapid evolution of women’s bathing costumes. They went from wearing long, heavy, woolen dresses with shoes and stockings in the late 19th century, to—gasp–exposing their arms and legs, and lowering their necklines by the 1920s.

It’s a fascinating theory, and I think it’s valid. But I also think that railroads made a huge contribution to this co-evolutionary fashion. Rail travel made it possible for many more people to make a day trip to the seaside, which had once been the province of the super-wealthy.

(All images from Library of Congress.)