According to Discover Magazine, a survey of more than 1,000 horror films shown in Britain between 1931 and 1984 found that scientists or their creations were the villains in 41 percent of the films. Only eleven of the films depicted scientists as heroes.

The Poop on Lewis and Clark

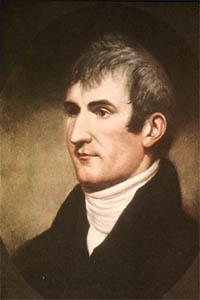

My eighth grader’s history textbook allocates half a page to Lewis and Clark. It explains in painfully dull detail how in 1803 President Jefferson sent the expedition to explore the new territory he’d just bought from the French (hello, how about mentioning Napoleon?). Lewis and Clark, the book drones on, were sent to find a route across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, and to collect information on people, plants, animals and geography.

So I thought today I’d touch upon some of the details of the expedition that kids might actually find interesting. For instance, the members of the expedition were practically driven insane by bugs, and they nearly died of starvation, and Lewis got shot in the butt and chased by a grizzly bear. And they were accompanied through the wilderness by a sixteen-year-old Indian girl carrying her infant on her back. Oh yes and pretty much everyone in the party had malaria and dysentery from time to time, and most had syphilis. But arguably the worst part of this arduous journey was the mosquitoes, followed closely by the gnats and ticks.

One other awful yet interesting detail you don’t generally read about in the textbooks: Upon his return, Lewis took his own life by shooting himself and then slashing himself with a razor blade.* (Other historians say he might have been shot by bandits. I think that’s unlikely, but we may never know for sure.)

Meriwether Lewis was a part-time botanist and doctor. William Clark was the mapmaker and boat guy. At the time they set out, few people of European descent had ventured beyond the Mississippi River and–to my knowledge–no European had trekked from East to West all the way to the Pacific Ocean. In fact, most Americans lived within fifty miles of the East Coast.

According to “The Perils of Plant Collecting” by A. M. Martin, Lewis spent 1/3 of his budget on cinchona (from which quinine is derived), mosquito nets, and hog’s lard (with which they had to smear their skin to keep away mosquitoes). Mosquitoes were so thick, people had to eat their food in the smoke of the campfire, and still they managed to swallow dozens of mosquitoes with their food. No wonder they carried 120 gallons of whiskey along. (Says Martin, “Lewis’s motto was ‘Don’t run out of booze until there’s no turning back.’”)

Given that their diet consisted largely of dried strips of wild animal meat, they also popped pills for constipation. They called the pills “thunderclappers.” Their real name was “Dr. Rush’s Bilious Pills.” (Benjamin Rush was a famous doctor at the time of the American Revolution, and signed the Declaration of Independence.) Thunderclappers were high-octane laxatives, made of 60 percent mercury. Even back then, people knew that mercury was terrible for you, and one pill contained enough mercury to kill a person. But the pill passed through a person’s system so quickly, it probably didn’t have much opportunity to be absorbed. Because mercury doesn’t break down, modern scientists have been able to trace the path of Lewis and Clark’s expedition by the amounts of mercury still found in the soil—evidence of where members of the expedition stopped to go to the bathroom. Talk about toxic waste.

___________________

* source: Howard I. Kushner, The Suicide of Meriwether Lewis: A Psychoanalytic Inquiry, The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 38, No. 3, Jul., 1981, Page 469 of 464-481 also Stephen Ambrose, Undaunted Courage, Touchstone, 1996, page 475

Decompressed

During World War I, as more and more women joined the workforce, corsets quickly went out of fashion. Enough steel was salvaged from corset stays to build two battleships.

Remote Chance

According to microbiologist Chuck Gerba, television remotes are the leading carriers of bacteria in a hospital room, worse than the toilet handles, bathroom doors, and call buttons.

He’s Pretty Slick

Macassar Oil was marketed as “an unguent for the hair” in 1807 by an advertiser who claimed it was made from sweet-smelling oils imported from Macassar (on the island of Celebes in what is now Indonesia). The stuff was probably made from coconut or palm oil and other fragrances.

Macassar Oil was marketed as “an unguent for the hair” in 1807 by an advertiser who claimed it was made from sweet-smelling oils imported from Macassar (on the island of Celebes in what is now Indonesia). The stuff was probably made from coconut or palm oil and other fragrances.

The fashion for men to oil their hair reached a peak in the mid-1800s. Because it had a tendency to transfer from the back of a gentleman’s head to the back of the chair in which he was sitting, housewives began covering the backs of their sofas and chairs with a protective cloth, or “antimacassar.” Elaborately crocheted antimacassars have become associated with Victorian frou-frou décor.

Yen for Beetles

Rhinoceros beetles are popular pets for children in Japan. In 1999, a Japanese company began selling live beetles from vending machines.

Poorhouses

On Monday I blogged about debtors’ prisons, which people often confuse with poorhouses, the subject of today’s cheery blog. Debtors’ prisons and poorhouses were not the same thing, but were equally dismal places.

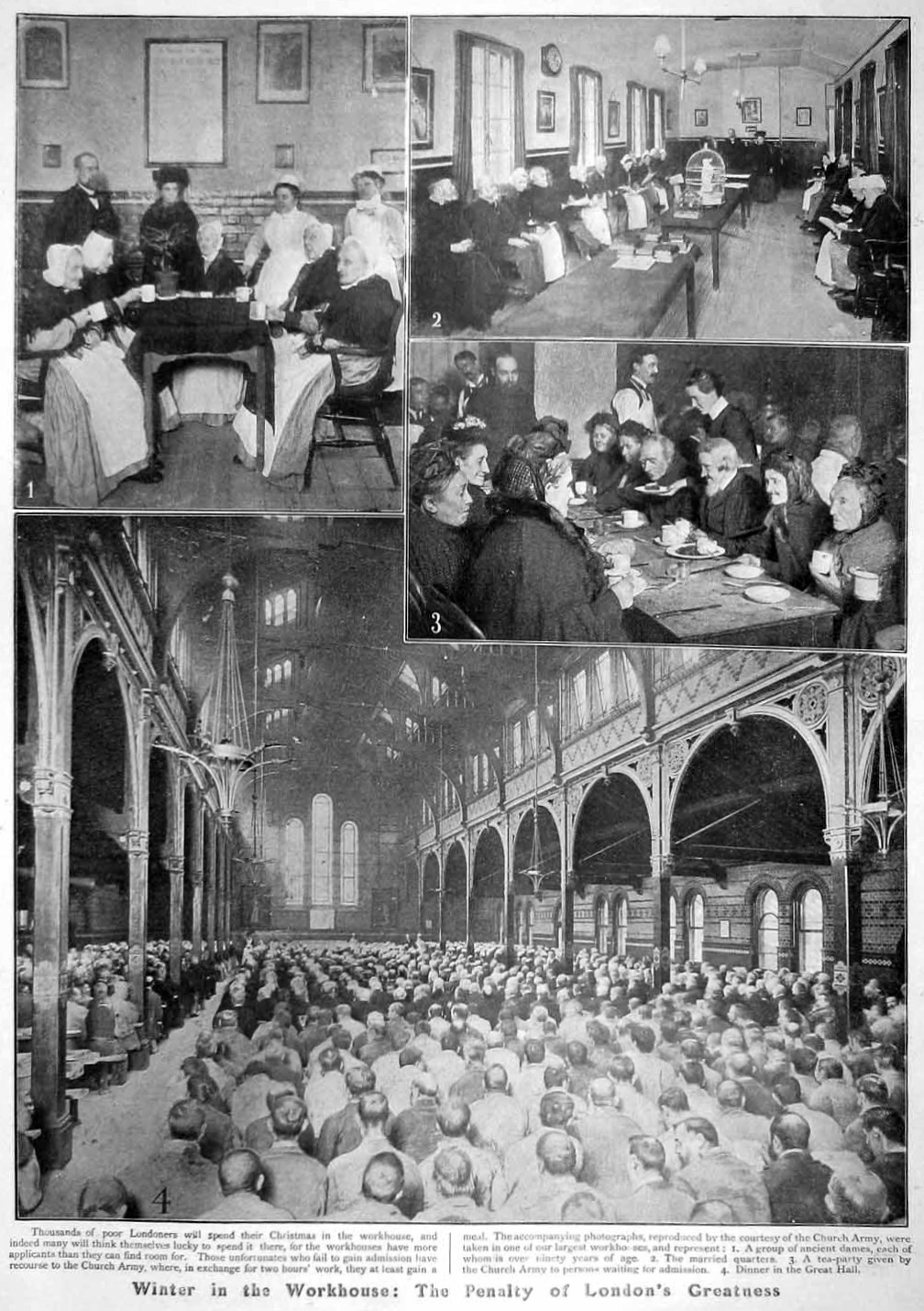

Poorhouses, or almshouses, existed in England from as far back as 1188, when Newgate Prison was built. (Lots of other European countries had poorhouses as well.) Workhouses started out as slightly different from poorhouses; they were more for reprobates and delinquents and drunkards, but during the 19th century the terms workhouse and poorhouse were often used interchangeably. In England, under the Poor Law of 1834, more and more of these grim places were built to house the poor. They were widely feared and thought to be avoided at all costs.

Inmates were required to surrender their clothes and wear standard workhouse uniforms. Food was dismal and scarce, and contagious disease common, especially with a population that tended to be pretty sickly to begin with. Idleness was thought to be dangerous, so inmates were required to spend their days in mind-numbing work like picking apart old rope, called oakum.

In colonial America, poor relief was heavily modeled on the British system. According to Michael Katz’s harrowing book, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, the poor in early America were dealt with in one of three ways: they were either auctioned off to the lowest bidder (theoretically to work for that employer, although it was effectively a form of slavery), driven out of town (if they weren’t local), or sent to the dreaded poorhouse.

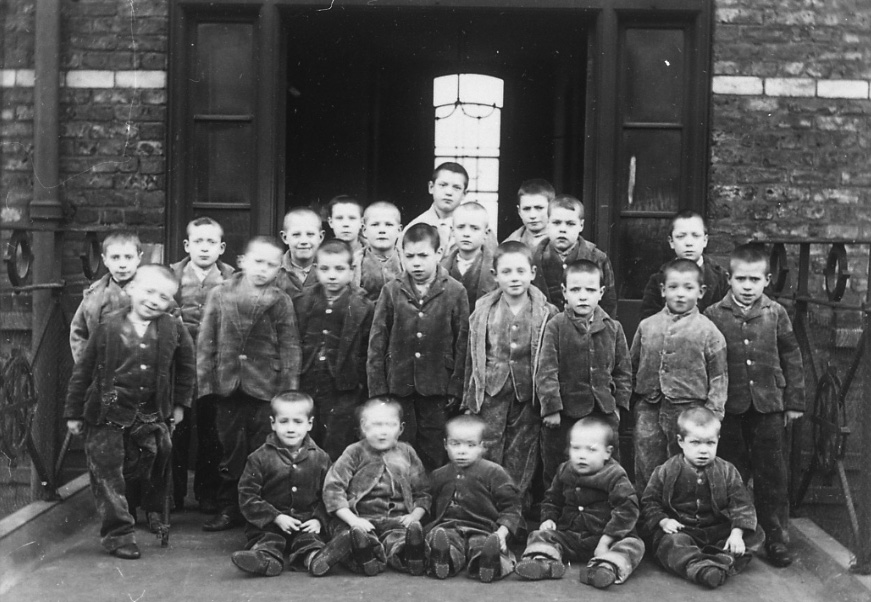

Life in the poorhouse was wretched, to say the least. The sparse meals consisted of watery gruel or bread and cheese. Baths were permitted once a week, and once inside, families were usually put into separate dormitories and parents were only allowed to see their children (over the age of 2) once a week, for a brief time. Orphans were often sent out to work as apprentices—just as Oliver Twist did.

The populations of the poorhouses grew rapidly in America during the nineteenth century, in part because of increased mechanization and the resulting loss of jobs, swelling immigration, and galloping epidemics of contagious disease that often killed off able-bodied wage earners and left families destitute. Most laborers had to live in walking distance of their jobs, because there wasn’t yet cheap public transportation. So they became destitute quickly if they lost their jobs. And women tended to be paid much lower wages than men. So the populations in poorhouses tended to tip more heavily toward women and children. There was no social security, welfare, or any other federal safety nets. Any charitable help was locally-based.

During the eighteenth century, most American cities and larger towns had poorhouses, including Boston, Salem, Portsmouth New Hampshire, Newport, Rhode Island, Philadelphia, New York City, Charlestown, Providence, and Baltimore.

Curses!

In Roman bathhouses, bathers often had their clothing stolen. In the absence of a police force, victims wrote curse tablets, calling on the gods to retrieve the stolen clothing or, barring that, to punish the thief.

Chop Chop

Frederic Chopin never entered a room left foot first. And sudden surprises made his hair stand on end.

source: Kathleen Krull, Lives of the Musicians, p 33

Get Out of Jail Free

I love being a kid’s writer. It’s the best job in the world, for a bajillion reasons. But the life of a freelancer can be pretty uneven, financially. It can take weeks—more often months—to get paid for work long finished. The worst part of the job is waiting for publishers to Send The Check.

During a recent rough patch when we were waiting for a Check and were searching in the couch cushions for change to buy milk, my thoughts turned to the old days, and what happened to debtors.

In ancient Rome, debtors usually ended up as slaves. In medieval England until well into the nineteenth century, debtors were thrown into debtors’ prisons, miserable places where you stayed without a preordained sentence. You were there until your debts were paid. Thieves and murderers received food and bedding and fuel from their jailors (well, at least until their executions). Debtors got nothing—and also had to pay their prison fees. In most debtors’ prisons, there were grated windows through which the debtor might shove a tin cup out to passers by in hopes of receiving some money to pay off his debt.

According to this fascinating article in the New Yorker by Jill Lepore, (4/13/2009) debtors founded our country. Two thirds of eighteenth century Europeans that came to America were debtors. The colony of Georgia, founded in 1732, was created largely for debtors released from English prisons.

You think of these places as grim Victorian institutions, found only in England. Not true. In mid-eighteenth-century New York City, debtors were imprisoned on the upper floors of a building near Wall Street. They would lower their shoes on a string out the window to collect alms for their own release. Well over half of them owed under twenty shillings.

There are lots of famous people who lived in debtors’ prisons, either for their own debts or for those of their fathers, including Charles Dickens, Samuel Johnson, William Hogarth, Daniel Defoe, and Henry Fielding. (Since women couldn’t own property, they couldn’t be debtors–but wives and children often lived in the prison with their debtor husband/father.)

Debtors’ prisons were abolished in the US in 1833, and in England during the 1860s. But lest you think they’re a thing of the past, think again. According to this piece by NPR, you can still be thrown into prison for unpaid bills in the US, and according to this article in the New York Times, there are other countries where you can land in jail for debts, as well.

By the way, the check did arrive, and I was able to pay off our bills and still have enough left over for a double tall latte.

Next blog—poorhouses!