On Monday I blogged about debtors’ prisons, which people often confuse with poorhouses, the subject of today’s cheery blog. Debtors’ prisons and poorhouses were not the same thing, but were equally dismal places.

Poorhouses, or almshouses, existed in England from as far back as 1188, when Newgate Prison was built. (Lots of other European countries had poorhouses as well.) Workhouses started out as slightly different from poorhouses; they were more for reprobates and delinquents and drunkards, but during the 19th century the terms workhouse and poorhouse were often used interchangeably. In England, under the Poor Law of 1834, more and more of these grim places were built to house the poor. They were widely feared and thought to be avoided at all costs.

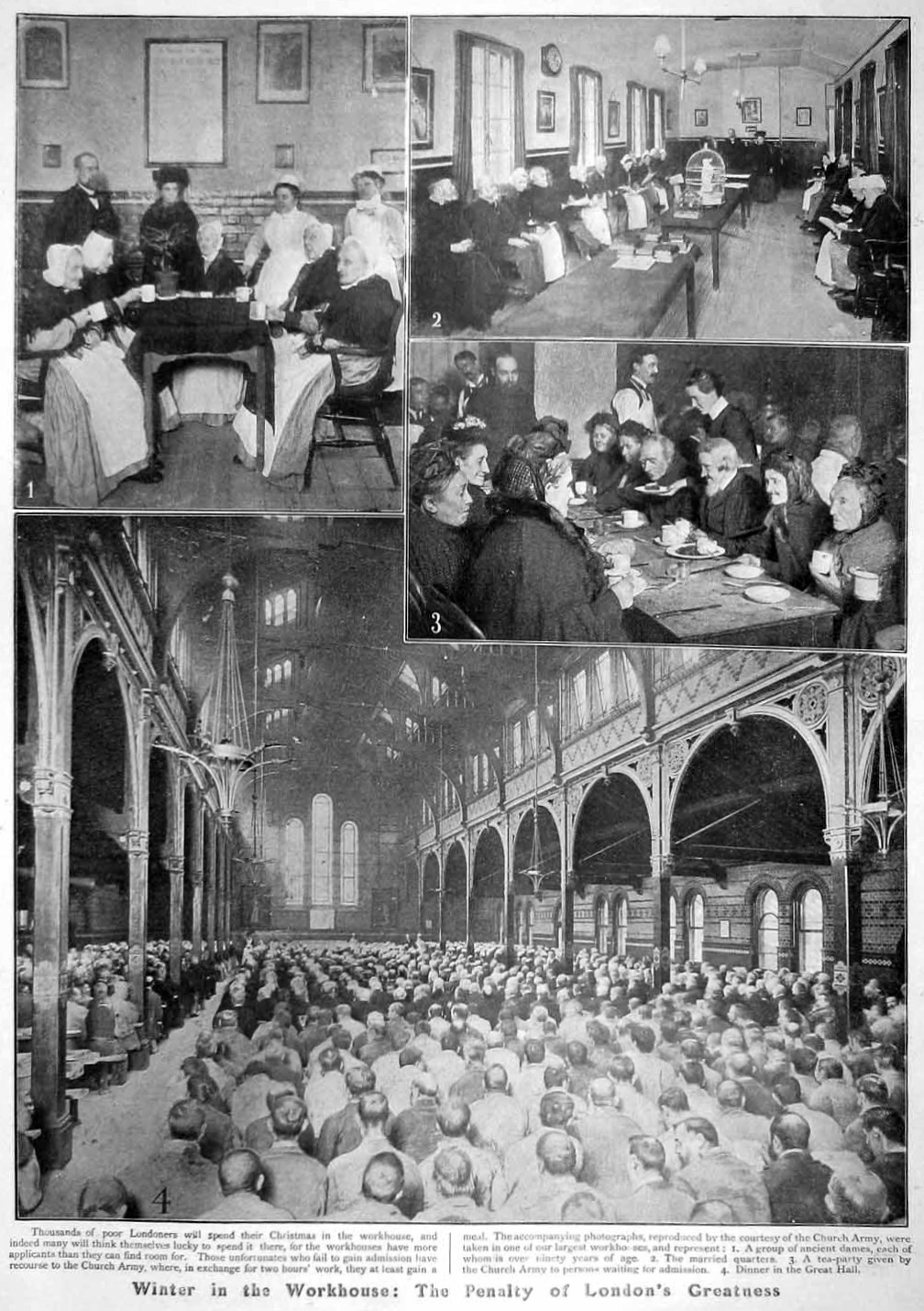

Inmates were required to surrender their clothes and wear standard workhouse uniforms. Food was dismal and scarce, and contagious disease common, especially with a population that tended to be pretty sickly to begin with. Idleness was thought to be dangerous, so inmates were required to spend their days in mind-numbing work like picking apart old rope, called oakum.

In colonial America, poor relief was heavily modeled on the British system. According to Michael Katz’s harrowing book, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, the poor in early America were dealt with in one of three ways: they were either auctioned off to the lowest bidder (theoretically to work for that employer, although it was effectively a form of slavery), driven out of town (if they weren’t local), or sent to the dreaded poorhouse.

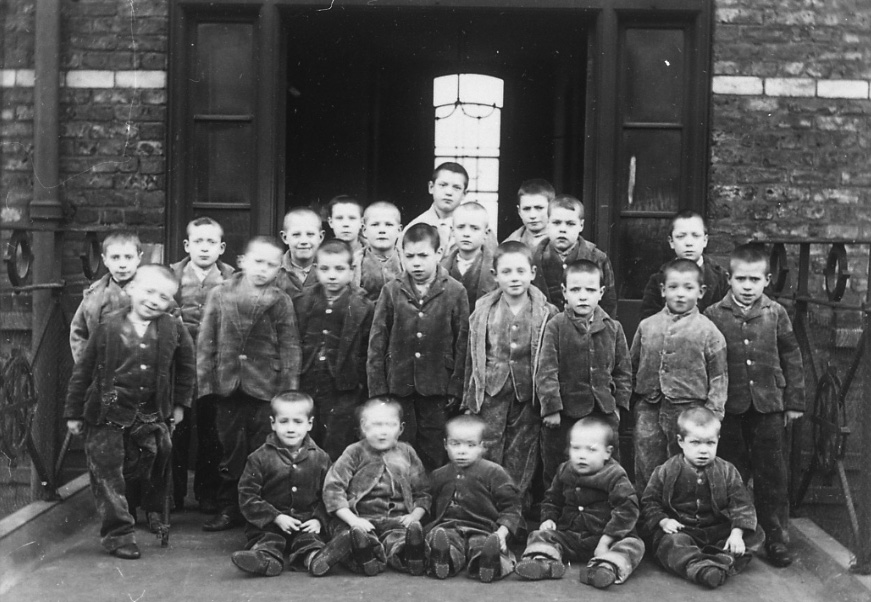

Life in the poorhouse was wretched, to say the least. The sparse meals consisted of watery gruel or bread and cheese. Baths were permitted once a week, and once inside, families were usually put into separate dormitories and parents were only allowed to see their children (over the age of 2) once a week, for a brief time. Orphans were often sent out to work as apprentices—just as Oliver Twist did.

The populations of the poorhouses grew rapidly in America during the nineteenth century, in part because of increased mechanization and the resulting loss of jobs, swelling immigration, and galloping epidemics of contagious disease that often killed off able-bodied wage earners and left families destitute. Most laborers had to live in walking distance of their jobs, because there wasn’t yet cheap public transportation. So they became destitute quickly if they lost their jobs. And women tended to be paid much lower wages than men. So the populations in poorhouses tended to tip more heavily toward women and children. There was no social security, welfare, or any other federal safety nets. Any charitable help was locally-based.

During the eighteenth century, most American cities and larger towns had poorhouses, including Boston, Salem, Portsmouth New Hampshire, Newport, Rhode Island, Philadelphia, New York City, Charlestown, Providence, and Baltimore.