In Shakespeare’s day, every man, woman, and child averaged a gallon of alcoholic beverages per day.

Toilet Talk

Thomas Crapper did not invent the modern toilet. But he was a very good plumber who improved upon the technology with several refinements to the design.

Powder Rooms

Eighteenth century powder rooms did not contain toilets. They were places where a person could have his wig oiled and powdered. A servant would puff flour over his master’s head with a bellows.

How D’ye Do?

Ever wonder why men bow and women curtsy? Corsets and pins, that’s why.

Fashion has dictated the habit: to bow properly, a man should bend from the waist. Historically, it was hard to do much else if you were wearing a tight corset, and men wore these well into the nineteenth century. Similarly, a woman’s careless curtsy could result in a shower of pins if she weren’t careful; not only would she be wearing a corset, or stays, or a stomacher, or a busk, or a combination of these, but with her overskirt painstakingly pinned to her farthingale or crinoline or hooped underdress, the most prudent way to pay obeisance to one’s social superior was to sink down slowly, vertically, and cautiously, a technique that seemed to dislodge the fewest number of pins.

Pash the Peash Pleash

Colonial Americans rarely drank water at mealtimes. Common beverages were whiskey, rum, beer, hard cider, and brandy.

Wake Up!

My friend Will sent me this fascinating article, which suggests that eight hours of sleep for most adults is not necessarily the ideal. As any parent of a small baby will tell you, we seem to be naturally inclined to sleep in four-hour chunks.

According to the article, a psychiatrist conducted an experiment where a group of people were plunged into darkness for 14 hours a day for a month. They eventually settled into a pattern of four hours of sleep, one or two hours of wakefulness, and then a second four-hour sleep.

It seems that for centuries, people used to sleep this way, and a historian found hundreds of references to this “first sleep” and “second sleep” pattern. The period between first and second sleep was a time to pray, walk around, or socialize with the throngs of people who might be sharing your bed.

By the seventeenth century, the pattern began to change, in part because cities began to use street lighting, and because coffee houses became popular (I’ll blog about those soon—they’re fascinating).

House Divided

The Pentagon, headquarters of the U.S. Department of Defense, was constructed during WWII. It was built with segregated bathrooms due to Virginia’s racial segregation laws.

Peachy

Melba toast and Peach Melba were named after opera singer Nellie Melba (1861 – 1931). Her image also appears on the Australian $100 bill.

Don’t Eat Your Greens

Avoid cooking potatoes that have green bits (and don’t eat green potato chips). They contain a natural toxin called solanine, which protects the plant from insects, disease and predators. Solanine can be harmful, especially to small children.

Poo Dans La Rue

I recently had a load of cow manure delivered to my back yard by a local farmer. It wasn’t smelly or anything. It had been aged and composted and was quite beautiful to behold, if you go in for that sort of thing. Like crumbled chocolate cake.

I recently had a load of cow manure delivered to my back yard by a local farmer. It wasn’t smelly or anything. It had been aged and composted and was quite beautiful to behold, if you go in for that sort of thing. Like crumbled chocolate cake.

As I spent a delightful couple of hours turning it into my vegetable garden, I got to thinking about the age-old tradition of using poop as fertilizer. Most people are reasonably comfortable with the idea that farmers use cow manure to fertilize their crops. But for many centuries, farmers used human poop as well. (They still do today, but that’s for another post.)

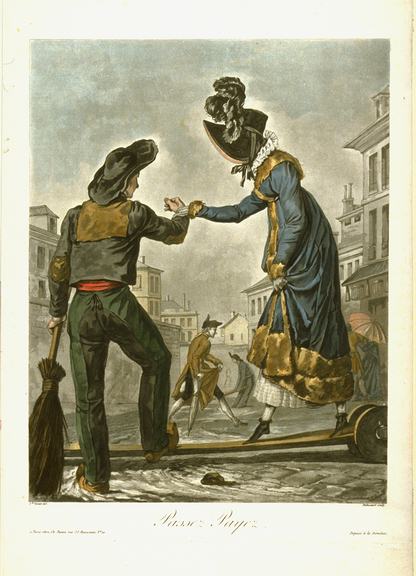

In Paris, a street sweeper called a pontonnier volant charged pedestrians a small fee to lay a plank across an open sewer. Louis-Philibert Debucourt (1755-1832), after Carle Vernet (1758-1835)

In medieval Paris, the “mud” collected from the city streets (which was impregnated with horse manure, person manure, and other vast quantities of rotting organic matter) was carted to the edge of the city and dumped over the walls. But as the mountains of waste got higher, city officials feared that besieging enemies would be able to run right up the piles of poop and scale the walls. So a dump was established a bit farther outside the city.

By the 18th-century, some of the waste collected from around Paris was brought to the dump, called Montfaucon, where it was aged through a process of open-air fermentation. The resulting “poudrette” was then collected by farmers and carted to fields. Montfaucon could be smelled for miles, especially on a breezy day.

But even with the dump, the streets of Paris suffered from a dismal lack of sanitation. There was no garbage collection in poor neighborhoods–and most of the aristocrats were living fifteen miles away, at Versailles. Tout a la rue was the governing principal of where to dump household garbage and chamber pots. Sewers were little more than open gullies running down the center of the streets, which of course overflowed and pooled in low-lying areas during heavy downpours. From time to time, taxes were collected to upgrade the sewers, but the king usually pocketed the proceeds for other things.

According to Donald Reid’s book Paris Sewers and Sewermen, high on the list of the Third Estate’s 1789 cahiers de doléances was a plea for upgrading the sewers. It was ignored. And you wonder why there was a revolution.

_________________

source: Reid, Paris Sewers and Sewermen