I recently had a load of cow manure delivered to my back yard by a local farmer. It wasn’t smelly or anything. It had been aged and composted and was quite beautiful to behold, if you go in for that sort of thing. Like crumbled chocolate cake.

I recently had a load of cow manure delivered to my back yard by a local farmer. It wasn’t smelly or anything. It had been aged and composted and was quite beautiful to behold, if you go in for that sort of thing. Like crumbled chocolate cake.

As I spent a delightful couple of hours turning it into my vegetable garden, I got to thinking about the age-old tradition of using poop as fertilizer. Most people are reasonably comfortable with the idea that farmers use cow manure to fertilize their crops. But for many centuries, farmers used human poop as well. (They still do today, but that’s for another post.)

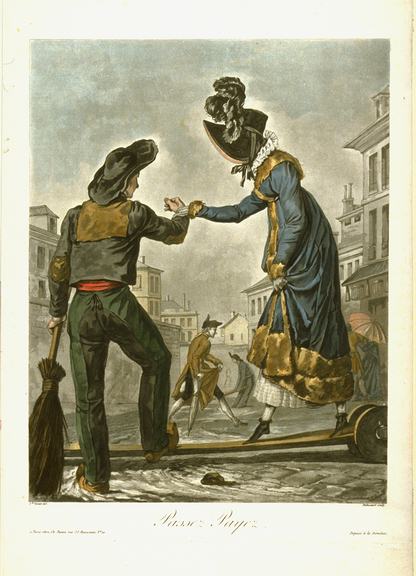

In Paris, a street sweeper called a pontonnier volant charged pedestrians a small fee to lay a plank across an open sewer. Louis-Philibert Debucourt (1755-1832), after Carle Vernet (1758-1835)

In medieval Paris, the “mud” collected from the city streets (which was impregnated with horse manure, person manure, and other vast quantities of rotting organic matter) was carted to the edge of the city and dumped over the walls. But as the mountains of waste got higher, city officials feared that besieging enemies would be able to run right up the piles of poop and scale the walls. So a dump was established a bit farther outside the city.

By the 18th-century, some of the waste collected from around Paris was brought to the dump, called Montfaucon, where it was aged through a process of open-air fermentation. The resulting “poudrette” was then collected by farmers and carted to fields. Montfaucon could be smelled for miles, especially on a breezy day.

But even with the dump, the streets of Paris suffered from a dismal lack of sanitation. There was no garbage collection in poor neighborhoods–and most of the aristocrats were living fifteen miles away, at Versailles. Tout a la rue was the governing principal of where to dump household garbage and chamber pots. Sewers were little more than open gullies running down the center of the streets, which of course overflowed and pooled in low-lying areas during heavy downpours. From time to time, taxes were collected to upgrade the sewers, but the king usually pocketed the proceeds for other things.

According to Donald Reid’s book Paris Sewers and Sewermen, high on the list of the Third Estate’s 1789 cahiers de doléances was a plea for upgrading the sewers. It was ignored. And you wonder why there was a revolution.

_________________

source: Reid, Paris Sewers and Sewermen