Arctic explorer Robert Peary, who reached the North Pole in April, 1909, lost eight toes to frostbite.

Oh, Honey Don’t!

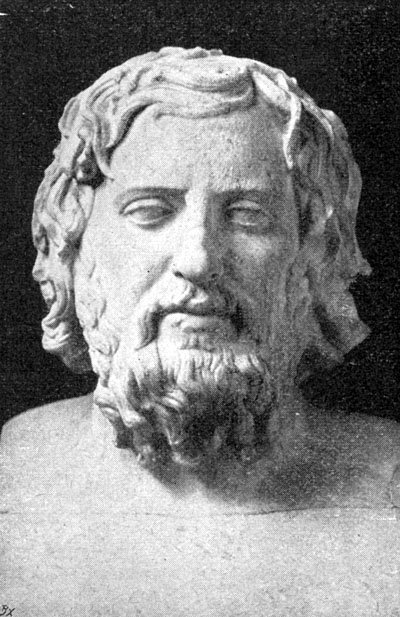

The 10,000-man Greek army, led by its general, Xenophon, was heading home from a battle with Persia in 401 BC when the weary men pitched camp in a lovely area called Trabzon, near the Black Sea. There they feasted on wild honey, which was abundant in the area. Soon after, the men collapsed by the thousands with dizziness, nausea, blurred vision, a lurching gait, and finally, an almost entire loss of muscle control.

The 10,000-man Greek army, led by its general, Xenophon, was heading home from a battle with Persia in 401 BC when the weary men pitched camp in a lovely area called Trabzon, near the Black Sea. There they feasted on wild honey, which was abundant in the area. Soon after, the men collapsed by the thousands with dizziness, nausea, blurred vision, a lurching gait, and finally, an almost entire loss of muscle control.

The army had been poisoned by the toxic honey, which had been made by bees collecting nectar from poisonous (to humans) rhododendron blossoms.

The men were sick for several days, but finally managed to recover enough to continue their march back to Greece.

The men were sick for several days, but finally managed to recover enough to continue their march back to Greece.

In 67 BC, King Mithradates of Persia faced a Roman force that was far superior, led by Roman General Pompey. But Mithradates was familiar with the writings of Xenophon. He lured the Roman army toward Trabzon. The Romans feasted on the poisonous honey, fell ill, and were massacred by Mithradates’ army.

images:

Xenophon, via Wikimedia

Bee in a rhododendron, By Earth100 (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Oh, Smack!

Ancient Romans sealed treaties with a mutual kiss on the cheek, called an osculum pacis. Persians sealed their deals with a direct kiss on the lips.

Adrienne Mayor, The Poison King, page 226

Movie Stars

The most-often filmed fictional human character is Sherlock Holmes, who has appeared in 226 different movies. The most-often-filmed nonhuman character is Dracula, who has been in 239 movies.

Thanks to interesting literature: Ten Facts about Sherlock Holmes

Crash Test

In 1912, an inventor who claimed to have invented a coat parachute tested his invention by leaping from the first deck of the Eiffel Tower. He was killed in the attempt.

The Prince and the Painter

Prince Balthasar Charles—or Baltasar Carlos in Spanish– (b. 1629) was the only son of King Philip IV of Spain and his first wife, Elizabeth of France. He was the heir to the Spanish throne and because he was such a beautiful child, he was beloved at the Spanish court. He is kind of a minor player in the vast and confusing and interrelated group that comprised the 17th century European monarchy, but he has become immortalized because he was the subject of a series of portraits painted by Velazquez (1599 – 1660).

I love Velazquez, and I especially love how much he clearly loved to paint this beautiful boy. Velazquez painted a bunch of portraits of him, beginning when the prince was two, until he was sixteen. In the prince’s later years, you can see the famous prominent Hapsburg chin (which I blogged about here), but he remained beautiful—at least as Velazquez saw him.

On October 5th, 1646, when the prince was sixteen, he fell ill with a fever—probably smallpox—and died four days later.

On a side note, in the first painting, the two-year-old prince is the one in the red sash wearing a dress (I blogged about boys in dresses here), and yes, that is a court dwarf in the foreground. Philip IV was especially fond of dwarfs, and more than a hundred lived at his court.

I thought I’d post some of these paintings (all via Wikipedia), just because I love them and want you to love them, too.

Poison Testers

Chinese rulers during the Han Dynasty often ate with silver chopsticks, believing that silver would tarnish quickly if it came into contact with arsenic (and other poisons).

Fighting for their Freedom

During the Revolutionary War, as many as half of the enslaved African adult males in Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia fled their masters to fight on the side of the British, believing they had a better chance at freedom than with the American side.

Wood Waste

About 25 billion disposable chopsticks per year are used in Japan—an average of 200 pairs per person. China produces about 45 billion pairs of disposable chopsticks a year—that’s about 25 million trees.

Source: NBC news

Where Do You Get Your Ideas, Will?

As any ninth grader who’s slogged through Julius Caesar can tell you, Shakespeare borrowed some of his plots from history. But at least two of Shakespeare’s plays were probably inspired by current events from his own day.

He wrote The Merchant of Venice in 1597. If you haven’t read or seen the play, one of the central characters is a man named Shylock, famously Jewish. He’s a controversial character, and Shakespearean scholars are divided about whether he’s a good guy or a bad guy—it’s considered a “problem play” because it’s unclear whether the play endorses or criticizes anti-Semitic proclivities. But for sure, Shakespeare wrote some of his most beautiful speeches for Shylock’s character—who is deeply flawed but deeply human.

He wrote The Merchant of Venice in 1597. If you haven’t read or seen the play, one of the central characters is a man named Shylock, famously Jewish. He’s a controversial character, and Shakespearean scholars are divided about whether he’s a good guy or a bad guy—it’s considered a “problem play” because it’s unclear whether the play endorses or criticizes anti-Semitic proclivities. But for sure, Shakespeare wrote some of his most beautiful speeches for Shylock’s character—who is deeply flawed but deeply human.

Shylock may well have been based on a real person, a contemporary of Shakespeare’s. That person was Rodrigo Lopez (1525 – 1594), a Portuguese Jew who converted to Christianity during the Portuguese Inquisition (a horrible period of history, which I may eventually blog about when I have the stomach for it). He became Personal Physician to the Stars, including Robert Dudley (Queen Elizabeth’s “favorite”) and, eventually, to the queen herself.

Lopez grew prosperous and famous, but in 1593 was accused of conspiring to poison the queen. He maintained his innocence to the end, and the queen herself delayed signing his death warrant for many months, but in June of 1594 he was hanged, drawn, and quartered. (If you don’t know what that is, be grateful.) Shakespeare would almost definitely have known about Lopez. Three years after Lopez’s execution, he wrote The Merchant of Venice.

Meanwhile, another current event may have given Shakespeare the idea for another play, The Tempest (1611).

In 1607, he’d already written three of his great tragedies—Hamlet, Macbeth, and Othello—when the Jamestown colony was established in the New World. In June, 1609, a fleet of supply ships sailed from England to deliver desperately-needed provisions (and an influx of new settlers) to the starving Jamestown colonists. The fleet was hit with a monstrous hurricane, and the flagship, Sea Venture, was wrecked near Bermuda. The castaways were stranded for months on a remote island, but they found food there, repaired their ship, and made it to Jamestown several months later.

In 1607, he’d already written three of his great tragedies—Hamlet, Macbeth, and Othello—when the Jamestown colony was established in the New World. In June, 1609, a fleet of supply ships sailed from England to deliver desperately-needed provisions (and an influx of new settlers) to the starving Jamestown colonists. The fleet was hit with a monstrous hurricane, and the flagship, Sea Venture, was wrecked near Bermuda. The castaways were stranded for months on a remote island, but they found food there, repaired their ship, and made it to Jamestown several months later.

Shakespeare wrote The Tempest two years after this well-publicized event—about a group of castaways on a remote island. Coincidence? I think not.