On this day in 1777 Vermont declared independence from New York.

Honoring Gettysburg

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg, which took place on July 1 – 3, 1863. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which is one of the most famous speeches in American history, was delivered on November 18, 1863, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, four and a half months after the battle.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg, which took place on July 1 – 3, 1863. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which is one of the most famous speeches in American history, was delivered on November 18, 1863, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, four and a half months after the battle.

I learned some fascinating details about Lincoln’s speech in Allen Guelzo’s Gettysburg: The Last Invasion.

Despite being November, it was a warm, hazy day, and the crowds were so densely packed along the parade route up Cemetery Hill that several women, and at least one man, fainted. There were about 15,000 spectators present on that day.

Lincoln was still working on his remarks right up until the parade began, crossing out phrases, rewriting sentences, inserting new words. (478) In an early draft, Lincoln planned to open with “How long ago is it?—eighty odd years?” He changed it to the more Biblical sounding “Four score and seven years ago…”

And here’s another cool fact. Lincoln had to have been familiar with a speech given by Speaker of the House Galusha Grow on July 4, 1861, which was widely disseminated. It began like this:

Fourscore years ago, fifty-six bold merchants, farmers, lawyers, and mechanics, the representatives of a few feeble colonists, scattered along the Atlantic sea-board, met in convention to found a new empire, based on the inalienable rights of man.

I mean, please. Compare the rhythm and cadence of the above passage with the opening of Lincoln’s speech. It’s pretty strikingly similar, isn’t it? According to Guelzo, Lincoln had no problem adopting and improving upon other people’s speeches. (479)

On that day in Gettysburg, Lincoln was preceded by the orator Edward Everett, who delivered a 13,000-word, two-hour snoozer. (Lincoln wasn’t a fan of Everett’s—he once described the orator as one of the most overrated public speakers in America.)

After Everett finally sat down, the president stood up and delivered his address in a little over two and a half minutes. A photographer trying to take Lincoln’s picture didn’t even have time to get his wet glass plate ready to capture an image.

If you want to read Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, you can find it here.

Kepler’s Demons

The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) is one of the founders of modern astronomy. Among other accomplishments, he identified three laws that describe planetary motion.

The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) is one of the founders of modern astronomy. Among other accomplishments, he identified three laws that describe planetary motion.

Kepler was born in a small German town and was educated in a church-school. He had a strife-filled family life. His great-aunt on his mother’s side had been accused of witchcraft and burned at the stake. Kepler was born premature, and contracted smallpox as a small child, which left him with bad vision and semi-crippled hands. His father, a mercenary, may have died in a war in the Netherlands when Kepler was about five—in any case, he never came home. His mother was an amateur apothecary/healer/herablist—which would later be an issue.

Professionally, Kepler was a product of his times. He was an early advocate of Copernican’s sun-centered theory, but also an astrologer-in-chief to the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph II of Prague.

This was a time when most people believed that astronomy and astrology were closely intertwined. It was a time when most people also believed in witches and ogres and demons. How else to explain the all-too-common deaths of children (Kepler himself lost many of his own children to disease), or the sudden sicknesses of cattle?

Kepler’s own mother, at age 70, gave someone an herbal remedy that made that person sick—and was arrested for witchcraft. Kepler battled her accusers from 1615 to 1621, when he at last secured her release. She died soon after.

Pop Culture

People living along the coast of Peru were eating popcorn as long ago as 3-6000 years ago.

http://newsdesk.si.edu/releases/ancient-popcorn-discovered-peru

Taking a Stand

On this day in 1777, Vermont became the first American colony to abolish slavery.

Skating Disaster

On January 6, 1867, the ice on the lake in Regent’s Park in London cracked abruptly, plunging more than 250 ice skaters into the water, which was over 12 feet deep in places. Forty skaters died.

Conan and Oscar

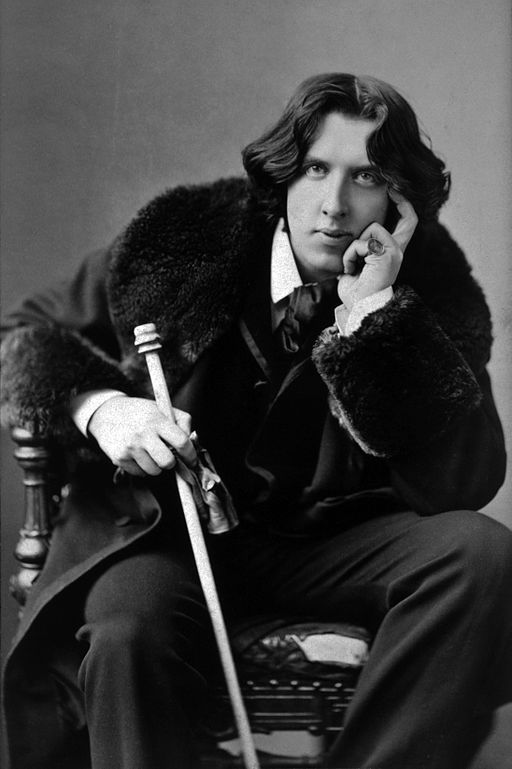

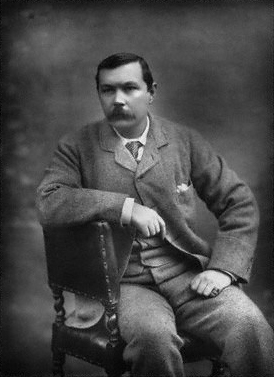

On August 30th, 1889, the managing editor of Lippincott’s, an American literary magazine, came to London. The editor, J.M. Stoddart, was recruiting authors to write for a British version of the magazine. He threw a dinner party at the elegant Langham Hotel, and invited two young writers named Oscar Wilde and Conan Doyle. The two had never met. At the time, Doyle had published one novel—“A Study in Scarlet”—introducing the private detective, Sherlock Holmes. It had been published in the magazine Beeton’s Christmas Annual, and had been reasonably well-received, although far from a blockbuster. Wilde, an Irish playright and author, was already famous.

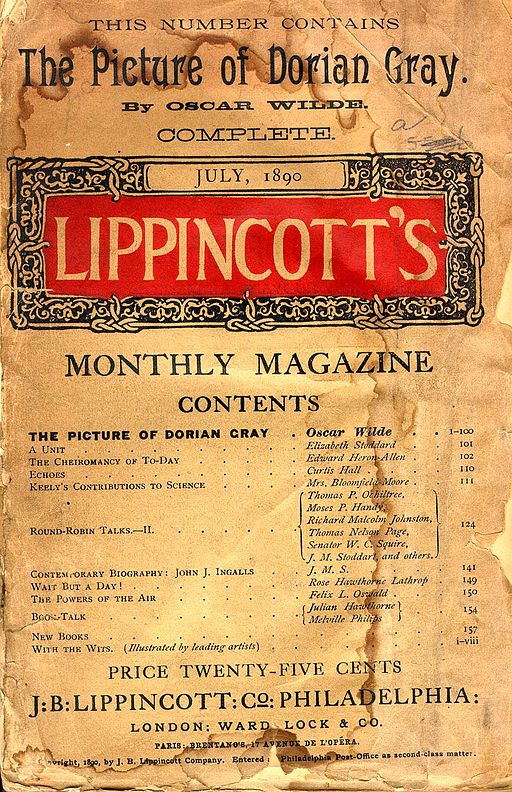

During the dinner, Stoddart convinced the two writers to submit stories to the magazine, which became a turning point in both their careers. Wilde went on to write The Picture of Dorian Gray, which appeared in the magazine a few months later, in 1890, and which Wilde later rewrote and expanded into a book version that came out in 1891. Doyle submitted his second Sherlock Holmes story ever, “The Sign of the Four,” which was a breakout success.

During the dinner, Stoddart convinced the two writers to submit stories to the magazine, which became a turning point in both their careers. Wilde went on to write The Picture of Dorian Gray, which appeared in the magazine a few months later, in 1890, and which Wilde later rewrote and expanded into a book version that came out in 1891. Doyle submitted his second Sherlock Holmes story ever, “The Sign of the Four,” which was a breakout success.

source: Smithsonian.com http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/Sherlock-Holmes-London.html?c=y&page=1

Oscar Wilde, 1882, by Napoleon Sarony [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Conan Doyle, 1893, by Herbert Rose Barraud (1845 – c1896) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Top Dog

This is my dog, Rosie. I’m not going to claim that she’s the best dog on the planet, because I’m sure some of you think you know a dog that fits that description, so I’ll just say she’s among the top dogs on the planet. She’s gentle with kids, playful with any kind of dog, wicked smart, and an excellent foot-warmer.

This is my dog, Rosie. I’m not going to claim that she’s the best dog on the planet, because I’m sure some of you think you know a dog that fits that description, so I’ll just say she’s among the top dogs on the planet. She’s gentle with kids, playful with any kind of dog, wicked smart, and an excellent foot-warmer.

I am now the proud owner of a treadmill desk, but for the past several years, the desk in my office was a built-in L-shaped thing, occupying one corner of the room. All last winter, Rosie’s bed was nestled in the corner underneath the desk, and she liked to sleep there while I worked. (Now she sleeps next to my treadmill, occasionally looking up and cocking her head at me in bewilderment.) My office is drafty on cold winter days, so I got into the habit of slipping off my shoes or slippers and burrowing my feet underneath her. (I also sometimes come home to find her sleeping on the bed–but she usually charms me out of getting mad at her.)

I did not know that there’s a long history of dogs who performed the task of foot-warmers and lap warmers. Lapdogs were welcomed into cold, drafty cathedrals and often were placed at the feet to keep the owner’s feet warm. According to this source, small dogs were also welcomed into the bed to warm it up, act as a heating pad, and to attract fleas from the human occupant to the dog.

I did not know that there’s a long history of dogs who performed the task of foot-warmers and lap warmers. Lapdogs were welcomed into cold, drafty cathedrals and often were placed at the feet to keep the owner’s feet warm. According to this source, small dogs were also welcomed into the bed to warm it up, act as a heating pad, and to attract fleas from the human occupant to the dog.

On Wednesday I blogged about turnspit dogs, those unfortunate canines that toiled away in the kitchens of large houses, operating a treadmill that was attached to the turning spit. According to Stanley Coren’s The Pawprints of History, turnspit dogs didn’t even get Sundays off. They were often taken to church to serve as foot warmers during the long services in the cold, drafty houses of worship. According to Coren, witnesses reported that one Sunday, the Bishop of Gloucester was preaching from the Book of Ezekiel and shouted, “It was then that Ezekiel saw the wheel.” At the mention of the word “wheel,” several of the turnspit dogs clapped their tails between their legs and ran out of the church.

On Wednesday I blogged about turnspit dogs, those unfortunate canines that toiled away in the kitchens of large houses, operating a treadmill that was attached to the turning spit. According to Stanley Coren’s The Pawprints of History, turnspit dogs didn’t even get Sundays off. They were often taken to church to serve as foot warmers during the long services in the cold, drafty houses of worship. According to Coren, witnesses reported that one Sunday, the Bishop of Gloucester was preaching from the Book of Ezekiel and shouted, “It was then that Ezekiel saw the wheel.” At the mention of the word “wheel,” several of the turnspit dogs clapped their tails between their legs and ran out of the church.

Johann Rudolf Huber, 1735, via Wikimedia Commons

Johann Rudolf Huber, 1735, via Wikimedia Commons

Lorenzo Costa, 1500, via Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt, 1665, via Wikimedia Commons

Quite a Shock

The business partner of Thomas Edison, Franklin Leonard Pope, was an electrical engineer and inventor of the stock ticker. Pope accidentally electrocuted himself in the basement of his home in 1895.

Center of the Universe

In 1633, Galileo Galilei was forced by Church authorities to recant his statement that the Earth orbits the Sun. On October 31, 1992, the Vatican admitted it was wrong.