Do you know where Patagonia is located? (And no, I don’t mean the store in Freeport, Maine.) It’s the region at the southernmost tip of South America, where modern-day Argentina and Chile are located.

The first explorer to name it Patagonia was probably Amerigo Vespucci, around 1500, although according to Felipe Fernandez-Armesto’s fascinating biography of Vespucci, so much of what Vespucci wrote was embellished with unreliable details (either by him or by his editors), so it’s hard to know if he actually visited Patagonia. But twenty years later, in 1520, the explorer Ferdinand Magellan spent the winter there with his fleet. He would surely have known about Vespucci’s voyage there, and he, too, called the locals Patagão, or Patagóns or Pathagoni.

The first explorer to name it Patagonia was probably Amerigo Vespucci, around 1500, although according to Felipe Fernandez-Armesto’s fascinating biography of Vespucci, so much of what Vespucci wrote was embellished with unreliable details (either by him or by his editors), so it’s hard to know if he actually visited Patagonia. But twenty years later, in 1520, the explorer Ferdinand Magellan spent the winter there with his fleet. He would surely have known about Vespucci’s voyage there, and he, too, called the locals Patagão, or Patagóns or Pathagoni.

The etymology is a little uncertain, but it basically means “people with big feet” or “giants.” According to the story told by Magellan’s chronicler, Antonio Pigafetta, the natives they encountered were extremely tall—Pigafetta estimated they stood between 9 and 12 feet. (Pigafetta was one of the few who literally lived to tell the tale–he was one of only nineteen sailors who survived the voyage around the world–you can read my blog about that here).

The myth captured the imaginations of Europeans for a long time.

A hundred years after Magellan, Sir Francis Drake’s chronicler confirmed Pigafetta’s account, but reduced the giants’ size down to a mere seven and a half feet.

It’s likely that the natives the Europeans encountered were the Tehuelche Indians, who were tall. Obviously not giants, but at least taller than the Europeans, which wasn’t saying much–the average sixteenth century European male was about 5′ 6 1/2″ tall.

Women in Elizabeth’s court wore removable sleeves, which were often highly ornamented and which could be sewn onto different bodices. They also sometimes wore a strip of jewel-encrusted embroidery along the hem of their gown, or down the front where the overskirt parted, which was removable but had to be sewn onto each skirt she wore. They were called “borders.”

Women in Elizabeth’s court wore removable sleeves, which were often highly ornamented and which could be sewn onto different bodices. They also sometimes wore a strip of jewel-encrusted embroidery along the hem of their gown, or down the front where the overskirt parted, which was removable but had to be sewn onto each skirt she wore. They were called “borders.” In Liza Picard’s

In Liza Picard’s  Aside from being a funny story, what’s remarkable is the detail about having to have your way lit for you—and how dark something like a theater staircase could be. I blogged about link boys

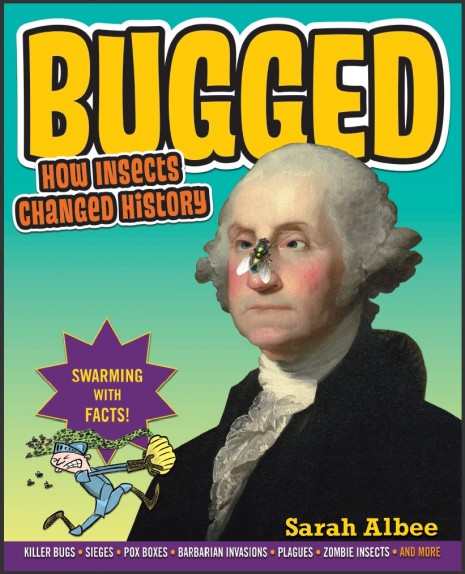

Aside from being a funny story, what’s remarkable is the detail about having to have your way lit for you—and how dark something like a theater staircase could be. I blogged about link boys  For the story about how the cover came to be, please click through to yesterday’s post at

For the story about how the cover came to be, please click through to yesterday’s post at  In AD 98, the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus (56 – 117) wrote a text called “About the Origin and Mores of the Germanic Peoples,” or Germania, as it came to be called. All copies of Germania were lost during the Middle Ages, but a single, hand-lettered copy resurfaced at an Abbey in present-day Germany in 1455. It was brought to Italy.

In AD 98, the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus (56 – 117) wrote a text called “About the Origin and Mores of the Germanic Peoples,” or Germania, as it came to be called. All copies of Germania were lost during the Middle Ages, but a single, hand-lettered copy resurfaced at an Abbey in present-day Germany in 1455. It was brought to Italy. Senator Warren G. Harding was nominated as the Republican presidential candidate in June of 1920, largely as a compromise after the three top contenders posed a political deadlock. Harding was seen as the best, albeit second-rate, option.

Senator Warren G. Harding was nominated as the Republican presidential candidate in June of 1920, largely as a compromise after the three top contenders posed a political deadlock. Harding was seen as the best, albeit second-rate, option.