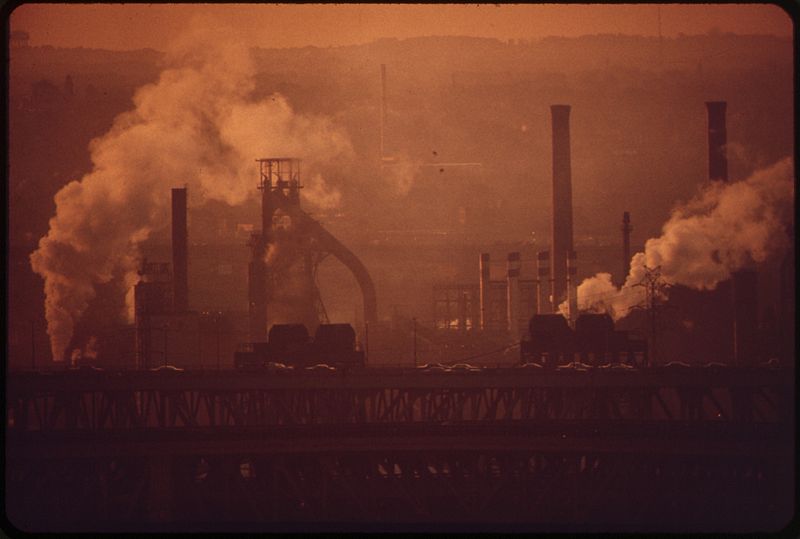

SUNRISE IN STEEL MILL SMOKE, 07/1973 Frank J. Aleksandrowicz, National Archives ARC Identifier 550181

From time to time you read about industry lobbyists who pressure our government into easing some of the regulations on factories to reduce smog-causing chemicals. These regulations were put in place for very good reasons, and the idea that the government might loosen them should horrify you. As recently as 1948, before any clean air standards were in place, before there was an Environmental Protection Agency, people literally choked to death from polluted air. And even today, in countries without such legislation, people are dying from air pollution.

Do I sound shrill? I’ve been doing a lot of research into this. My next few blogs will be all about smoky cities.

Ask any grownup about the Donora Death Fog, one of the worst environmental disasters in American history, and chances are, you’ll be greeted with a blank look. And the crazy thing is, it happened so recently.

Donora, Pennsylvania is a small, hilly town in a narrow river valley about twenty miles south of Pittsburgh. In 1948 it had about 14,000 residents, 5,000 of whom worked at the many factories in town. Most of the factories were steel mills owned by U.S. Steel, but there was also a large zinc smelting pant. These factories produced a lot of smoke, dust and gas containing dangerous levels of sulphuric acid, carbon monoxide, and other pollutants.

A few days before Halloween, 1948, a weird atmospheric phenomenon known as an inversion occurred. An inversion is when a pocket of warm air traps the colder air near the ground. In Donora during that time, there was no wind, which meant that rather than blowing away, the smog became trapped, down where people lived and breathed. Inversions still happen all the time—Los Angeles has them frequently. But the one that trapped the smog around Donora for five days in October was especially deadly.

At first nobody paid much attention. Residents were used to smog. It made for beautiful sunsets, and it was a sign of industry and employment. Most people had no idea that it was bad for you, even though practically nothing green grew within a half mile of the zinc plant. As the deadly fog rolled in, kids walked to school with a flashlight. Cars had to drive with headlights on during the daytime. People reported that they couldn’t see their own feet. But it wasn’t long before people realized this smog was different. People started dropping dead. By Saturday, October 30th, seventeen people were dead in the space of twelve hours, and others were gasping for breath. Half the town’s population became sick or hospitalized with respiratory problems. The fire department went door to door, administering oxygen to people who were too sick to leave. Many people fled, but some who tried to evacuate were caught in the heavy traffic caused by the fog. The exact toll from the smog has never been accurately calculated, but at the time, twenty people died, and thousands more lived the rest of their lives with permanently damaged lungs.

It wasn’t until October 31st that the mills shut down operations as “a precaution,” and then it rained, which almost immediately helped disperse the pollutants. But the factory owners never admitted wrongdoing. The companies colluded with the U.S. Public Health Service to cover up the tragedy, calling it “an Act of God,” and the facts were kept hidden from the public for over fifty years. Vital records disappeared from the archives, and to this day, U.S Steel continues to block access to their records from the time of the incident.

Pittsburgh escaped the fog, primarily because it had just begun to enact smoke control ordinances—which you can read about in my next blog.

The tragedy marked a turning point in the government’s attitude toward regulating clean air. In 1955 the Clean Air Act was passed.