Ever wonder why the color purple has long been known as the color reserved for royalty?

A sort-of purple cloak, favored by high-ranking ancient Romans,from "Costumes of All Nations," 1881 (via Wikimedia)

I’ve blogged before–actually a few times–about what a dismal job it was to be a textile dyer, over the course of centuries. Before the discovery of synthetic dyes in the mid-1800s, dying fabric was extremely complicated, dangerous, and smelly work. Dyers worked with corrosive acids, poisonous salts, and steaming vats of nasty-smelling muck.

Nowadays practically all fabric dye is produced synthetically in a laboratory, but prior to 1850 or so, colors could only be created with stuff found in nature. And for centuries, purple was the most rare and costly color of all.

Tyrian purple, as it came to be known, was produced by Phoenician people in the city of Tyre. They were known to the Greeks as Phoinikes, or the “Purple Men.” The Phoenicians lived in a coastal area east of Egypt on a strip of land in what is now Lebanon, from about 900 BC until 600 BC. Although the Minoans were probably the first to make purple, back in 2500 BC, it was the Phoenicians who produced enough of the stuff to trade and grow prosperous.

Tyrian purple was sought after by Roman Emperors and imperial monarchs throughout Asia. And it came from a rather unlikely source: snail snot.

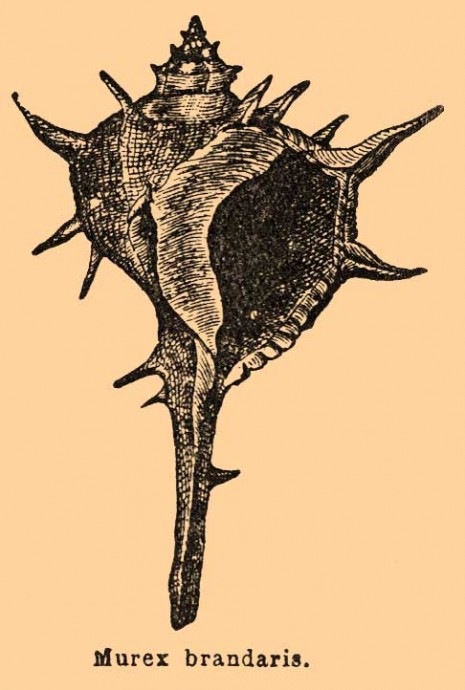

Muricids are gastropods whose hypobranchial gland secretes a mucusey substance that turns different colors when exposed to sunlight. Tyrian purple was produced from a mollusk known as Murex brandaris.

The Phoenicians established beachside dye centers wherever they found significant populations of these shells.

Each Murex brandaris produces just two drops of a milky-looking secretion. Dyers had to crush thousands of shells to produce enough dye for just one toga. After being smooshed, the mollusks were left in the sun to rot. The oozy slime they secreted was painstakingly collected. By carefully timing its exposure to sunlight, dyers created colors from green to violet to red, to the most prized, an almost-black purple. The smell from the rotting mollusks was so atrocious that no one could bear to live nearby.

Eventually, Tyrian purple was replaced by a new purple dye that was much less costly to produce. The new dye was made from a species of lichen. But the term royal purple remains part of our language to this day. It’s even in the Crayola crayon box.