Candlestick makers–or tallow chandlers as they were once called–led a wretched existence. I thought I’d make today’s blog about candle making, because I’m still without power.

Candlestick makers–or tallow chandlers as they were once called–led a wretched existence. I thought I’d make today’s blog about candle making, because I’m still without power.

Thanks to the freakishly violent October snowstorm we had over the weekend, and because I, along with 800,000 other CT residents, am on day God-knows-what without power, I have been doing a lot of reading by candlelight. Trust me: it’s overrated. I have wax drips in my bed and I think my eyeglass prescription has gone up a notch due to eyestrain. Thank goodness for the library, which blessedly has power, and heat.

For centuries candles could be made from beeswax, but beeswax was expensive. Candles used by ordinary people were made from tallow. Tallow is cattle and sheep fat—often rancid cattle and sheep fat. When melted, it smells unimaginably vile. The job of the candle maker—called a “tallow chandler”—was to hack the fat into chunks, melt it down, and dip a twisted wick into it. The result was known as “tallow dip.”

According to Emily Cockayne’s fascinating book, Hubbub: Filth, Noise and Stench in England, chandlers’ melting houses were often forbidden near residential areas. These laws were ignored, of course. Cockayne quotes a 17th-century writer who says “the smell was thought to be sufficiently potent to induce hysteria.” And 17th century noses were probably pretty tolerant of bad smells. It must have smelled quite horrible.

Haydn portrait by Thomas Hardy, 1792

On a lighter note (sorry)—candles were also used as clocks, burning at specific rates to measure the passage of time. Many classical symphonies last only as long as it took for candle chandeliers to be lowered and fresh candles installed.

Franz Josef Haydn wrote his Farewell Symphony to send a message to his patron, Prince Esterhazy. Evidently Haydn and his orchestra colleagues were eager to go on vacation, but the prince had detained them at his remote palace of Eszterhaza. In the final movement, Haydn instructs musicians to stop playing, one by one. Each part includes the instruction nicht mehr–“no more.” The player finishes his part, blows out the candle lighting his music stand, and then departs the stage, until only the conductor and a couple of violins are left.

Evidently the prince got the message, and the musicians were permitted to leave for vacation soon after the piece premiered.

UPDATE: I wrote this yesterday, and our power came back on last night! Hooray!!

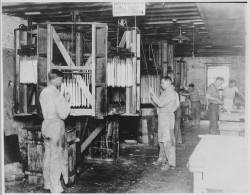

Above image: “Workmen hand-dipping candles at the Saint Louis Candle and Wax Company,” 1927, National Archive/Department of Agriculture