Livre d’heures de Jean de Montauban – Bibliothèque des Champs Libres

One of my favorite memories from childhood was opening a new box of crayons. I marveled at the beautiful hues. When I was older and took painting classes, I never lost that feeling of awe at the brilliant, saturated colors that came right out of the paint tube. But five hundred years ago, painters didn’t have the luxury of buying their paints from the art supply store. They had to mix their own colors. This was often difficult, expensive, or dangerous. Sometimes it was difficult, expensive and dangerous. What’s amazing is how they still managed to produce such intense, gorgeous colors.

First, to get the terms straight: the pigment is the coloring agent in paints. It usually came in powdered form and, pre 19th century, was almost always found in nature (animal-based, plant-based, or from naturally occurring minerals). Painters mixed the powdery pigment with a binding agent so that it could be applied as paint. Binding agents could be any number of things, but they included egg tempera, pine resin, gum arabic, honey, and even earwax.

Here are how some common colors from medieval and Renaissance times were produced. If you didn’t already appreciate beautiful paintings from these periods, you’ll surely do so now, just for the sheer energy it took to produce the colors. (It wasn’t always the artist himself who made the pigments, of course. It might have been his assistant, or someone else at the monastery.)

Reds

Many of the so-called “red lakes” were made from ground up insects. To produce them, painters boiled up the powdered, dried lac, kermes, or cochineal insects with urine or lye, and then mixed it with a binding agent.

Vermillion, another red color, was made from cinnabar, which is the principal ore of mercury. Or you could just heat together sulphur and mercury to form an artificial cinnabar. (Heating up mercury? Never a good plan.) Traces of cinnabar have been found in the bones of medieval scribes, and probably hastened them toward an early death.

Masters of the Dark Eyes Missal, Initial S with Presentation in the Temple, Walters Manuscript W.175, fol. 158v

Blues

Azurite was a deep blue pigment that contained arsenic sulphide, and creating it produced a toxic gas called mercury cyanide. It was expensive, but slightly cheaper than ultramarine, the most expensive pigment. Ultramarine was made by grinding up the precious stone lapis lazuli, and because it was so expensive it was reserved mostly for paintings of Christ and the Virgin.

The Wilton Diptych By Unknown Master, French (second half of 14th century) (Web Gallery of Art: via Wikimedia Commons

Gold was often used to gild manuscripts. The painter started with a base adherent and then carefully positioned the gold leaf on the page. After it dried, the excess was removed.

Aussem Hours, SS. Catherine and Barbara, with gold and floral marginal decoration, Walters Manuscript W.437, fol. 108v

Lamp black was made from soot or charcoal.

White lead pigment was made by suspending strips of lead over vinegar or urine inside a vase. The vase was sealed, and buried in a dung heap for a few days. A crust formed on the lead. It was scraped away and ground up.

Albrecht Durer, detail, Four Holy Men

Green pigments included verdegreen, malachite, and Spanish green. Many of these were derived from arsenical compounds and were highly toxic.

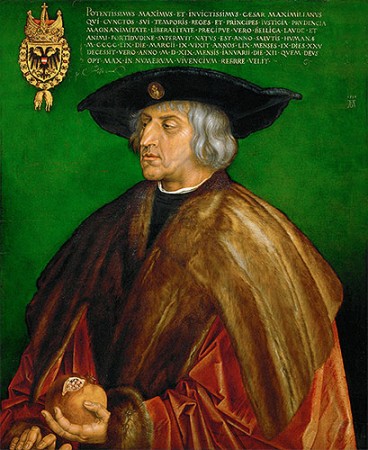

Albrecht Durer, Portrait of Maximilian I, 1519

Yellows

Orpiment, also called King’s Yellow, was made from a volcanic stone with a sparkly quality that was found all over the world. It was extremely poisonous, as it, too, contained arsenic.

Sources:

https://www.ischool.utexas.edu/~cochinea/pdfs/a-baker-04-pigments.pdf

http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/intro/history.html

http://www.jcsparks.com/painted/pigment-chem.html

http://web.princeton.edu/sites/ehs/artsafety/sec10.htm