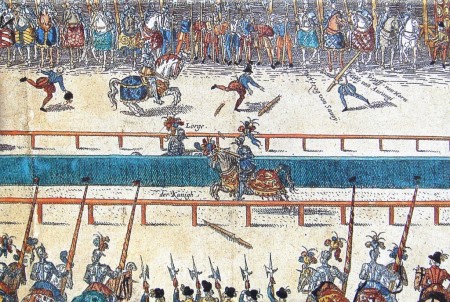

On a hot June day in 1559, King Henry II of France galloped toward his jousting opponent at full speed. His opponent was the young captain of his Scottish Guard, Gabriel Count de Montgomery. Montgomery had begged to be allowed to decline the joust, but King Henry had insisted.

The two horsemen met. There was a loud crack and Montgomery’s lance splintered. When they lowered the king to the ground and removed his helmet, they found a piece of wood had pierced his eye and another was protruding from his temple.

The two most celebrated physicians of the day were summoned: Andre Vesalius and Ambroise Parė. As the doomed king lay next to them, feverish and in agonizing pain, the two physicians put in a grisly room-service order: the severed heads of four recently executed criminals. They used these heads to try to re-create the king’s wounds.

Ten days later, he died, most likely of sepsis.

This story is not about what happened next—but what happened next, if you’re curious, is that Henry’s wife, Catherine de Medici, punted his long-time mistress, Diane de Poitiers, out the back door and went on to co-reign with a succession of three of their ten children—the frail Francis II, who died in 1560, the frailer Charles IX, who died in 1574, and the foppish and ineffectual Henry III, who would be murdered by a religious zealot in 1589.

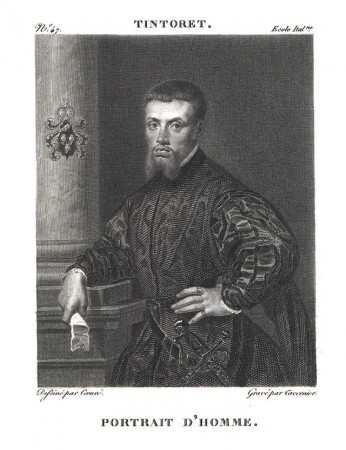

No, this story is more about the two rock-star doctors, Ambroise Parė and Andreas Vesalius.

Parė rose to fame as a result of his military surgical career. He’d discovered that battlefield patients who had received mild wound dressings made of eggs and oil of roses healed better than those who’d had corrosive acid or boiling oil poured onto their amputated stumps. Go figure. But this thinking was hot stuff at the time. This was a time when other surgeons believed that victims of gunshot wounds should be induced to sweat, so soldiers were buried in manure up to the neck. Not sure if that was before or after the boiling-oil-to-the-stump.

Vesalius was an eminent anatomist, which was saying something, because there were so few anatomists at the time. This was a time when surgeons had had very little opportunity to study anatomy using human cadavers, because it was against the law. Executed criminals were about the only corpses available, and there weren’t enough of them around. Most of the existing anatomy books were based on animal anatomy, rather than human. As a younger man, Vesalius had stolen bodies chained to gallows, and crept into cemeteries under cover of darkness, hiding bones under his coat for the purpose of studying them. Many medical schools were obliged to form dodgy alliances with grave robbers and murderers to be assured a supply of bodies for dissection. (You can read my blog post about that here.) But his tenacity paid off: Vesalius published a seven-volume, groundbreaking work on human anatomy.

Still, despite their combined expertise and experience, both doctors clearly felt some pressure not to mess up. Hence the decapitated heads in Henry’s sickroom. But poor Henry was beyond help.

My favorite story of Vesalius’s dissection lecture-demonstrations is when a group of his medical students found a corpse, and, to avoid the prying eyes of law-enforcers, they dressed it up, and “walked” it into the dissecting room, as though it were a drunken student being dragged into class.

Sources: Lois N. Magner, A History of Medicine. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. 1992

Leonie Frieda, Catherine de Medici, Renaissance Queen of France. New York: HarperCollins, 2003.