Nowadays, subdued colors are considered proper business attire, especially for men. But to people of the Renaissance, muted, earthy shades were the colors of poverty. Noblemen, princes and high church officials wore bright colors. The brighter the color you were wearing, the more important you were.

It wasn’t until bright colors became available to the masses—with the discovery of synthetic dyes in the mid-19th century—that blacks, grays, and navy became the colors of choice for the fashionable.

I learned a lot about the life of textile dyers in a fascinating book called A Perfect Red: Empire, Espionage, and the Quest for the Color of Desire, by Amy Butler Greenfield. As I’ve blogged about before, red was an extremely difficult color to obtain. It’s why popes and cardinals wore it. Deep red could be made from the ink of the murex snail (which also produced royal purple, another extremely expensive color), but it was the cochineal scale insect, discovered and stolen from the Aztecs by the Spanish conquistadors, that produced the brilliant scarlets so sought after by the wealthy.

Over the course of centuries, the life of a dyer was never a pleasant one. It was horrible work. The best dyers were highly sought after, but they lived low on the social ladder. It was extremely complicated, dangerous, and smelly work. Dyers worked with corrosive acids, poisonous salts, and steaming vats. Because bright colors faded quickly, dyers used chemical binding agents called “mordants” to prevent fading. And red wasn’t the only color fraught with danger, difficulty, or disgusting ingredients. To achieve blue, dyers used urine as an important ingredient. Indigo was harvested by slave labor, blue woad was incredibly smelly, and we already know how purple came from smooshed, rotten snails. Green (as I’ve blogged about before) was derived from a compound of arsenic.

When Mary, Queen of Scots walked to the execution block in 1587, she was dressed in a black gown with a white veil. But underneath it, she wore a red satin bodice and a red velvet petticoat. That was no accident. In Tudor England, red had a rich meaning. It was the color of martyrdom and royal blood.

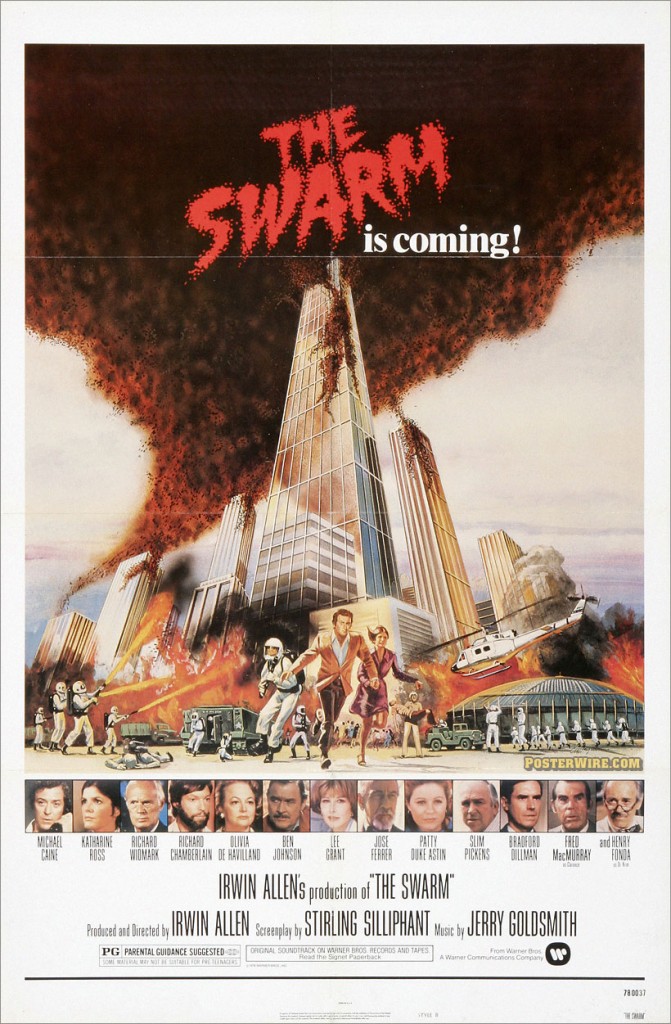

My loyal readers know that from time to time I review insect-themed horror films on this blog. It’s one way to understand the relationship between humans and insects. Today’s review: The Swarm (Warner Brothers, 1978).

My loyal readers know that from time to time I review insect-themed horror films on this blog. It’s one way to understand the relationship between humans and insects. Today’s review: The Swarm (Warner Brothers, 1978).