Carolus Linnaeus (aka Carl Linné) is best remembered for his system of scientific classification. He was not known for his generosity of spirit; those who criticized him were apt to find they had weeds named after them.

Carolus Linnaeus (aka Carl Linné) is best remembered for his system of scientific classification. He was not known for his generosity of spirit; those who criticized him were apt to find they had weeds named after them.

We were stuck in traffic a few times over the holiday. It’s a lot easier than it used to be, now that my kids are older. With little kids, traffic jams are horrible. The baby’s squalling, the toddler’s got to go to the bathroom, well, you know. But in the future, we may be able to avoid traffic jams. Scientists are working on a new technology for cars, based on . . . ants.

We were stuck in traffic a few times over the holiday. It’s a lot easier than it used to be, now that my kids are older. With little kids, traffic jams are horrible. The baby’s squalling, the toddler’s got to go to the bathroom, well, you know. But in the future, we may be able to avoid traffic jams. Scientists are working on a new technology for cars, based on . . . ants.

According to Discover Magazine, scientists threw roadblocks in front of leaf-cutter ants who then changed their leaf-gathering strategies to bypass the roadblock. The ants leave a trail of pheromones to show their fellow ants the best route back to the nest. By working together, they reinforce the trail using what entomologists call “distributed intelligence.”

Other scientists are working on copying ant ingenuity by using something called Inter-Vehicle communication, where cars send out signals to other cars when they slow down quickly—say, when entering a traffic jam. Other drivers close to the jam will know to slow down, and they in turn can send the message to vehicles to avoid the route altogether.

Here’s a pretty cool National Geographic video showing leaf cutter ants at work.

According to microbiologist Chuck Gerba, your toilet seat is considerably less germy than the door of your refrigerator.

People first started using needles about 10,000 BC. The needles were made from woolly-mammoth tusks, bird bones, fish bones, or bamboo. Thread was made from animal guts or hair.

Happy New Year, everyone!

Like most of you, we did a lot of cooking and entertaining over the holidays, with family and friends. Sometimes the seating plan at these holiday tables can be a little tricky, especially when you’re mixing your relatives with your friends.

I have this amazing cookbook written by Francine Segan called Shakespeare’s Kitchen: Renaissance Recipes for the Contemporary Cook, that includes authentic recipes from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It wasn’t all boiled mutton–the recipes are an amazing window into the way people lived at the time. According to Segan, cookbook authors assumed that a cook knew the proper amounts of ingredients. Recipes don’t include details more specific than “as your eye shall advise you,” and “as your cook’s mouth shall serve him.” She also includes some fascinating information about feasting and customs from Shakespeare’s day.

In Renaissance times, big-banquet seating in grander houses was very hierarchical; you instructed your page to seat people according to their rank, from duke to marquese to earl to bishop to viscount to baron to knight to squire.

It was considered quite improper to serve water at a feast. Water was stored in lead tanks so that the worst of the “mud” and whatever else it was polluted with could settle before it was drunk, but it tasted awful anyway. People used it for boiling meats and to make fermented drinks, which killed a lot of the germs.

So instead of water, the host served fermented alcoholic drinks like hard cider, ale, wine or beer—to men, women and children. From the time of the Middle Ages, toast was added to drinks to improve their flavor, and it was from that practice that the expression “drinking a toast” comes from.

Usually the kitchen was quite a hike from the feasting area—fire was a real hazard, of course, so in many manor houses and castles the kitchen was in a separate building. As a result, most food served at Renaissance feasts was room temperature.

Charlemagne’s successors were named Louis the Pious, Charles the Bald, Louis the Stammerer, Charles the Fat, and Charles the Simple.

Of all the cowboys who rode the cattle trails on the American frontier during the nineteenth century, nearly one out of every six was black.

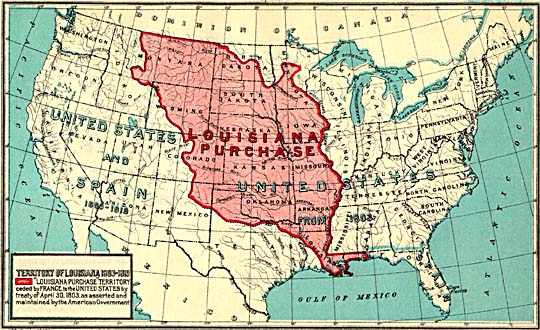

I was helping my middle schooler study for his big American History test a few days ago, which focused on westward expansion in the early nineteenth century—you know, Manifest Destiny, the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark, and including events leading to the Civil War and then the Civil War itself. (It was a big test.)

I was helping my middle schooler study for his big American History test a few days ago, which focused on westward expansion in the early nineteenth century—you know, Manifest Destiny, the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark, and including events leading to the Civil War and then the Civil War itself. (It was a big test.)

And here’s the crazy part: There was not a single mention of mosquitoes anywhere in his textbook. Not a one. I know, shocking. A huge reason Napoleon was content to punt 828,000 square miles of territory to Thomas Jefferson in 1803 was that he’d just suffered a major debacle in Haiti, losing tens of thousands of men (including his own brother in law) to mosquito-vectored malaria and yellow fever. (Of course, no one back then knew that mosquitoes transmitted these diseases.) The West Indies were a death trap for Europeans with no resistance to these diseases. He was more than happy to unload this territory—much of it nearly as pestilential as the West Indies—onto the clueless Americans for 15 million dollars, thinking he’d by far gotten the better deal, and no doubt laughed his way to la banque.

I could make this a very long blog entry, but I know that no one has time to read a lengthy exegesis about 19th-century America’s insect-vectored diseases this close to the holidays. Suffice to say, mosquitoes played a huge role during this period of our history. The cultural prejudices that were born during this time directly reflected the unbalanced malarial burdens suffered by those living above and below the Mason-Dixon line. The “hardworking,” “industrious” Northerners, who suffered relatively little malaria, considered Southerners lazy lie-abouts. In a 1785 letter, Thomas Jefferson described Southerners as “indolent,” “ unsteady,” and “fiery.” The Anopheles mosquito, the species that transmits malaria, helped create these deep cultural prejudices.

And the Civil War was “a giant malarial feast,” according to Sonia Shah in The Fever. Union troops suffered 1.3 million cases of malaria, and the mind boggles to think what the Confederate numbers must have been.

Deranged Roman Emperor Caligula (AD 37 – 41) was so sensitive about being bald that he made a law that no one could look down on him from a high place when he passed by, punishable by death.

A common Spartan meal was pork boiled in blood. The result was a sort of gooey, black, vile-tasting stew.