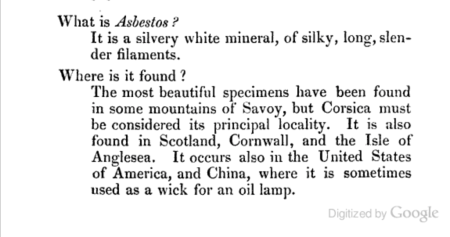

In this book from 1868 called The Guide to General Information on Common Things, written by “A Lady,” I stumbled across this entry called “What is Asbestos?”

Crashing the Party

If you think about it, it makes sense that roller skates were invented in Holland. After all, that was the land of ice skating on frozen canals, and putting wheels on your shoes was a great way to ice skate in the summer.

The first known inventor/improver of the roller skate was a Belgian named John Joseph Merlin (1735 – 1803). He was a mechanic by training, who concentrated on musical instruments, invalid chairs, and mechanical chariots. He moved from France to England in 1760, and soon after arriving in London, he decided to stage a dramatic entrance at a fancy masquerade party. He arrived wearing a pair of his metal-wheeled boots and playing the violin. But he hadn’t invented a way to turn or stop on his roller skates, and so he crashed into a large mirror lining the rear wall of the room, breaking the mirror and rather severely injuring himself.

http://www.rollerskatingmuseum.com/homework.html Reader’s Digest Everyday Life Through the Ages http://www.rc.umd.edu/gallery/john-joseph-merlin-the-celebrated-mechanic

I’ll Take Manhattan

I live in Connecticut, also known as the “Nutmeg State.” It finally occurred to me to look into how our state earned this moniker. It turns out the history of nutmeg is fraught with drama and horror. And what does all of this have to do with Manhattan? Read on.

Nutmeg is not a nut, but a seed of an evergreen tree called Myristica fragrans. The same tree also produces mace.

Nutmeg is not a nut, but a seed of an evergreen tree called Myristica fragrans. The same tree also produces mace.

It’s been a prized spice across cultures for centuries. Medieval and Renaissance societies thought it was an aphrodisiac and also believed it could ward off plague. Up until the mid-19th century, the only place you could find nutmeg was in Indonesia, on a small range of volcanic islands known as the Bandas. The smallest one, called Pulau Run (later called just “Run” by the Europeans) was chock-a-block with nutmeg trees. Arab traders sold nutmeg to Venetians for high prices, but kept the location a secret. Nutmeg was hugely expensive, and therefore a big status symbol for wealthy Europeans.

Finally in the early sixteenth century, the Portuguese invaded the area and discovered the source. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Dutch took over, and gained control of the islands. This is where the horror part comes in.

The Bandanese were coerced into signing a contract that stated they could only sell nutmeg to the Dutch, which gave the Dutch an effective monopoly on nutmeg. In exchange, they’d receive useless trade items, like heavy woolen cloth that was completely worthless in a tropical climate. Also, the soil conditions of the island were only suited for growing nutmeg, and not much else, And Bandanese nutmeg growers were used to trading nutmeg to neighboring islanders for things like, gee, food. Naturally, they went back to dealing with their usual Asian and European trading partners. The Dutch knew the treaty was impossible to comply with, but they used the Bandanese violation of it as an excuse to “step in.” In 1621 they executed forty of the leaders, put their heads on pikes, massacred most of the inhabitants of the island, forcibly expelled the rest, and imported slaves and convicts to do the work, overseen by Dutch plantation owners. It soon occurred to the Dutch that no one knew how to grow nutmeg, so the few remaining Bandanese that had been sent elsewhere were brought back as slaves and forced to share their expertise with nutmeg cultivation.

The Dutch established nutmeg plantations on several islands. This was a time when the Dutch and British were at constant battle for control of the spice trade—which in effect was control of the world, and at some point the British gained control over the island of Run.

Finally in 1667 the two powers signed a treaty. The Dutch wanted their nutmeg monopoly back, and also a part of South America controlled by the British that produced sugar. The British wanted the island of Manhattan. So they swapped. New Amsterdam became New York. The Dutch got their nutmeg and sugar.

Oh and as far as Connecticut being nicknamed the Nutmeg State? From what I can determine, it was rumored that some dishonest Connecticut traders tried selling fake nutmeg they’d whittled from wood. So I guess the nickname implies we’re “the fraudster state.” Nice. A more recent theory is that real nutmeg really is wood-like, and Connecticut traders were falsely deemed fraudsters by certain southerners who claimed they’d bought “fraudulent” nutmeg. But in fact they were unaware that it had to be grated.*

*http://mentalfloss.com/article/55245/why-connecticut-called-nutmeg-state

CARLSON D, JORDAN A. Visibility and Power: Preliminary Analysis of Social Control on a Bandanese Plantation Compound, Eastern Indonesia. Asian Perspectives: Journal Of Archeology For Asia & The Pacific [serial online]. Fall2013 2013;52(2):213-243. Available from: Academic Search Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed May 26, 2015.

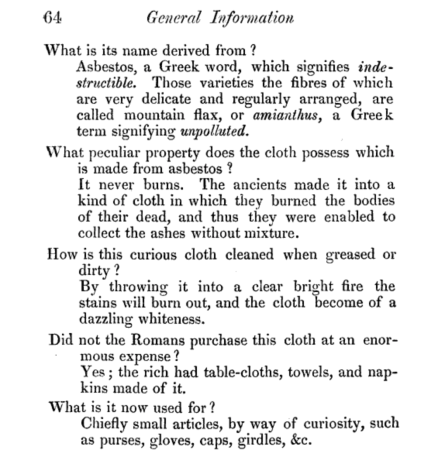

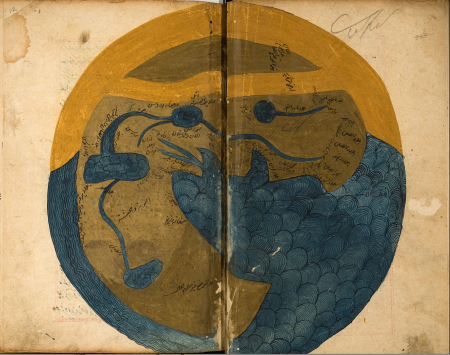

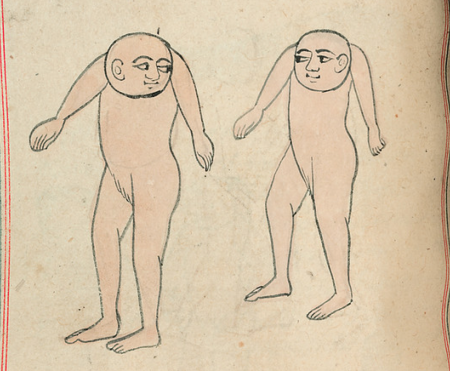

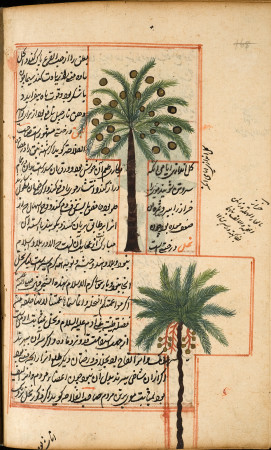

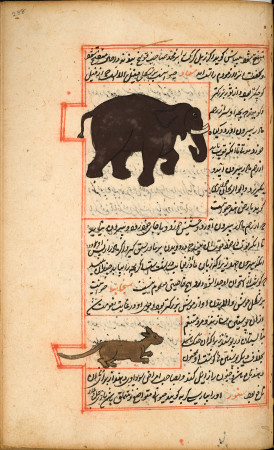

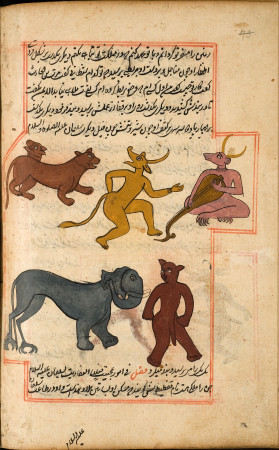

The Wonders of Creation

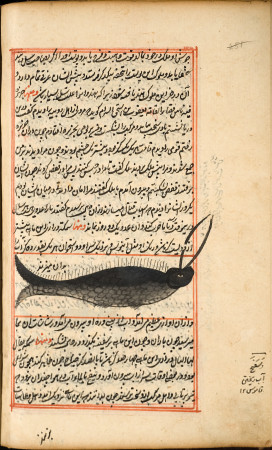

In this, the latest installment of the ongoing blog series I call “If I find my research fascinating, everyone else will, too,” I wanted to show you some images from a thirteenth century book.

In this, the latest installment of the ongoing blog series I call “If I find my research fascinating, everyone else will, too,” I wanted to show you some images from a thirteenth century book.

According to the NLM website, the original book was created by Abu Yahya Zakariya ibn Muhammad ibn Mahmud-al-Qazwini (ca. 1203-1283 CE) or just al-Qazwini to his friends, and is called Kitab Aja’ib al-makhluqat wa Gharaib al-Mawjudat, translated as “The Wonders of Creation.” You can go here and actually turn the virtual pages. It’s awesome. (Don’t forget you’d read the book from right to left.)

It was originally compiled in the middle 1200s in what is now Iran or Iraq. Says the NLM website, “The vibrantly illustrated work is considered one of the most important natural history texts of the medieval Islamic world.” A Persian translation was created in 1537, in what is now Pakistan. The pictures show exotic places and creatures. Al-Qazwini was known to be a good writer, who compiled his version of the terrestrial and extra-terrestrial world by collecting stories from the ancient world and from his contemporaries. What I love about these pictures, besides how beautiful and weirdly contemporary they are, is you can totally conjure up stories from the Odyssey and from the Arabian Nights–like the islands visited by Sinbad. I was obsessed with the the Odyssey and Arabian Nights as a kid. (See? I told you it’s all about me.)

A sampling for you:

Neckless humans from the NLM Flickr site: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nlmhmd/8616730368/

A Scar is Born

Practically everyone knows that Harry Potter received a lightning-shaped scar on his forehead, sustained as an infant when Voldemort tried to strike him dead with a killing curse. But what I didn’t know, until I recently read Adrienne Mayor’s fascinating book The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, is that Mithradates VI, king of Pontus (134 BC – 63 BC), also purportedly had a scar on his forehead–also sustained as an infant, when a bolt of lightning struck his crib. The scar was shaped like a diadem, or crown. According to contemporary chroniclers, the scar was considered a mark of divine ordination that he should grow up to become king. The diadem shape meant the gods had crowned him at birth. Mithradates was seen as a savior for the people of the near east and Asia Minor, who roundly hated being ruled by Rome.

I’ve got to think JK Rowling knew of this story.

The Great Connecticut Caper

Update: Last January I posted this blog about the Great Connecticut Caper. This is the second to last week of the story, and my chapter is now up. I have a guest post here at author Katie Carroll’s website. Also, if you live in Connecticut or close by, the final event will be June 7th at Gillette Castle, from 2 to 4. I hope to see some of you there!

Today I’m excited to announce that I am to be one of twelve authors (plus twelve illustrators) who will contribute to a serialized adventure story called The Great Connecticut Caper. Here’s the website, and here’s how it works:

Every two weeks, starting yesterday and running through June, a new chapter will be posted at the Connecticut Humanities website. (ctcaper.cthumanities.org)The basic plot will revolve around the famous Gillette Castle, which goes missing. (The Connecticut landmark was voted on and decided by kids and teachers, and Gillette Castle won.) A couple of 11-year-old kids must solve the case. Readers can contribute ideas to help solve the mystery and follow the clues on social media. No one knows how the mystery will end, because it hasn’t been written yet. (My chapter is second-to-last!)

The official launch party, hosted by Connecticut Humanities and the Wadsworth Atheneum, will be this Wednesday, January 7th, from 4:30 to 6:30. You can find out more and register here (it’s free!).

I was so happy when I learned that my audition piece had been selected. Several of my writer and artist friends are also participating. I hope you’ll check it out, even if you don’t live in Connecticut.

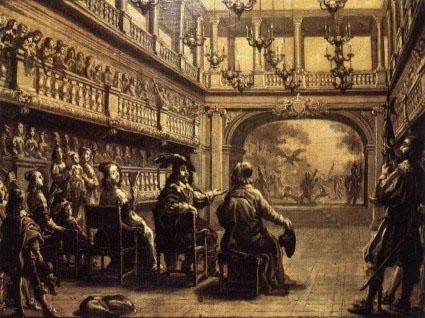

Candle-Opera

The world before electricity and gas lighting was a very dark place. If you could afford them–and most ordinary people couldn’t–oil lamps and candles made from beeswax shed some light. Most people made do with rush lights or smoky, smelly tallow.

The world before electricity and gas lighting was a very dark place. If you could afford them–and most ordinary people couldn’t–oil lamps and candles made from beeswax shed some light. Most people made do with rush lights or smoky, smelly tallow.

If you were of moderate income and could afford a single candle, your family would have spent a lot of quality time together. Your teenager couldn’t easily storm off to his room, at least not if he wanted to see. All of you would have to sit by the light of that single flame and read, sew, draw, or talk. Also the wicks of early candles were different from today. Candles had to be trimmed regularly—every ten minutes or so for wax, or as often as forty times an hour for tallow. Otherwise they’d get too hot, melt too much fat or wax, and “gutter,” or stream wastefully. In large homes and palaces this was a servant’s job.

Also the wicks of early candles were different from today. Candles had to be trimmed regularly—every ten minutes or so for wax, or as often as forty times an hour for tallow. Otherwise they’d get too hot, melt too much fat or wax, and “gutter,” or stream wastefully. In large homes and palaces this was a servant’s job.

In 1783 Ami Argand, a Swiss inventor, invented a new kind of oil lamp. It had a chimney that allowed more oxygen to circulate around the flame and therefore shed a lot more light than the old oil lamps. It also had a knob that adjusted the flame.

Which brings us to the stage. The new Argand lights were introduced to the Odeon theater in 1784 for the premier of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, and a year or so later, to the English theater, but they were expensive and it took a few years more before they were widely used in theaters and concert halls.

So prior to the late 1700s, composers and playwrights really had to think about candles when they were composing and writing. A candle could burn for roughly an hour. Composers knew that between acts in a play or an opera, candles had to be changed. And during performances, a human candle trimmer had to trim them regularly. Chandeliers had to be lifted and lowered on pulleys. Even so, actors and musicians must have had a lot of wax drip on them during a performance.

So prior to the late 1700s, composers and playwrights really had to think about candles when they were composing and writing. A candle could burn for roughly an hour. Composers knew that between acts in a play or an opera, candles had to be changed. And during performances, a human candle trimmer had to trim them regularly. Chandeliers had to be lifted and lowered on pulleys. Even so, actors and musicians must have had a lot of wax drip on them during a performance.

In 1772 (a decade before Argand Lamps), Haydn wrote his symphony #45. It was written for his patron, Prince Esterhazy, while Hadyn and the court orchestra were staying at the Prince’s summer palace. Haydn and his musicians were eager to go home. In the last movement, Haydn had each musician quietly blow out his candle and tiptoe off stage until just two musicians remained playing. It became known as the Farewell Symphony. Evidently the prince got the message and the court packed up and went home the next day.

If you visit this linkand click at about the 25 minute mark, you can see the musicians tiptoeing offstage. It’s pretty funny—and a beautiful piece of music.

http://www.compulite.com/stagelight/html/history-3/18-cen.html

Bill Bryson, At Home 140 - 146

Diorama Trauma

Today I have a guest post at Tara Altebrando‘s blog. Please visit here!

Crossing Swords (and Garters)

In the course of doing some image research I stumbled across this 1542 German how-to book on Athletic Arts, called Paulus Hector Mair’s De Arte Athletica.

I tried to translate some of the German descriptions with Google Translate but mostly what it gave me was text of this nature:

In gestracktem arm with obstructive deinam ever to face seinam He stands up to you so you unnd gögen with your right Fuoss In steest so far with your Rarpier on in the unnd nimb on your right side to be lincke lanngen with deinner

So I can’t enlighten you about the finer points of sword fighting, but what I love about the book are the fashions. Some 16th-century artist (Paulus?) lovingly painted over four hundred different scenes with each combatant wearing different athletic attire. This is one of my favorite fashion eras. You can see slashing, cross gartering, codpieces, peascod bellies, balloon trunks, and just general brilliant colors. Also notable is the appearance of a sword fighter of African descent, just as richly attired as the rest. Feast your eyes.

Rise Above

For most of pre-20th century fashion history, women’s hemlines did not rise above ground level. What a nightmare it must have been to clean the hems after a sojourn outdoors.

Here’s a fashion accessory you don’t come across much any more: the skirt-lifter (otherwise known as the dress-holder).

Here’s a fashion accessory you don’t come across much any more: the skirt-lifter (otherwise known as the dress-holder).

They were used by promenaders, croquet players, and, I have to think, anyone who wanted to keep her hemline in reasonable condition. They seem to have hit their peak when women took to bicycle riding in the 1890s. They were attached by a long chain to a woman’s belt, and shaped like tongs or pincers, and could catch and lock the hem of a woman’s skirt. The wearer would pull up on the chain and lift her skirt so that she could cross a dirty street, or climb stairs or trolley steps, or ride a bicycle.

They were used by promenaders, croquet players, and, I have to think, anyone who wanted to keep her hemline in reasonable condition. They seem to have hit their peak when women took to bicycle riding in the 1890s. They were attached by a long chain to a woman’s belt, and shaped like tongs or pincers, and could catch and lock the hem of a woman’s skirt. The wearer would pull up on the chain and lift her skirt so that she could cross a dirty street, or climb stairs or trolley steps, or ride a bicycle.

Images: Top paintings all from wikimedia. Skirt lifter images come from Etsy or Sotheby’s or this French for-sale site, and are offered for sale (and are therefore, I hope, permissible to post).