The Regent (later King Charles V, right) and the King of Navarre (Charles II the Bad, left) conferring in a tent. From the Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, BL Royal MS 20 C vii f. 135v

Meet Charles, King of Navarre (1332 – 1387), also known as Charles the Bad. Because he tried, unsuccessfully, to conquer both France and Spain, the French called him Charles Le Mauvais, and the Spanish, Carlos el Malo.

What was so “the bad” about him? A combination of unpopular taxation policies, endless treasonous plotting with the English to overthrow his father-in-law, Charles V, the king of France, and for a generally dissolute lifestyle. One of the guys he was known to hang out with was called Peter the Cruel (from Seville). Barbara Tuchman describes him as a “supreme troublemaker,” who was “absolutely without scruple.” (132)*

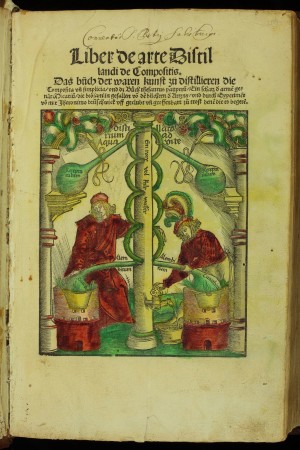

But it’s his gruesome death for which he is most remembered. On a winter night in 1386 he fell ill with chills and shivering. According to Tom Standage in his fascinating book, A History of the World in Six Glasses**, Le Mauvais’s doctor ordered him wrapped up in cloth. The doctor decided to try the new go-to medicine, distilled wine, known as aqua vitae. Distilled wine was way higher in alcohol than regular wine or other fermented drinks. At the time, it was thought that aqua vitae could be helpful either by having the patient drink it or by applying it topically to the affected areas—in the case of the debauched king, that meant his whole body, as he had fever and chills. The doctor opted for the topical approach. Oopsadaisy. (Other accounts say it was brandy, but I’m pretty sure brandy that’s been repeatedly distilled may be the same thing as aqua vitae.)

They soaked the king’s sheets with aqua vitae or maybe brandy, and wrapped him up from head to toe, to warm his body and induce sweating. But then, “One of the female [others say a male valet] attendants of the palace, charged to sew up the cloth that contained the patient, having come to the neck, the fixed point where she was to finish her seam, made a knot according to custom; but as there was still remaining an end of thread, instead of cutting it as usual with scissors, she had recourse to the candle, which immediately set fire to the whole cloth. Being terrified, she ran away, and abandoned the king, who was thus burnt alive in his own palace.”** He lived for two agonizing weeks before expiring.

* Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror [mine is the 1978 edition]

**History of the world in Six Glasses by Tom Standage page 98-100

***Francis Blagdon, 1803, Paris as it was and as it is: or, A sketch of the French capital, illustrative of the effects of the revolution, with respect to sciences, literature, arts, religion, education, manners, and amusements; comprising also a correct account of the most remarkable national establishments and public buildings

![V0010765 A young fashionable apothecary-surgeon(?) about to give a si Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org A young fashionable apothecary-surgeon(?) about to give a sick wealthy lady an enema. Engraving by A. Bosse, 16--. By: Abraham BossePublished: [16--] Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/](https://www.sarahalbeebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/edd6c23756eee34ae968ecb19614-450x353.jpg)

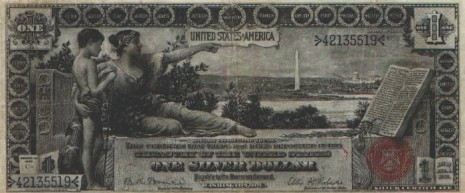

Here’s the back of the one-dollar bill. It shows George and Martha Washington (there’s a refreshing concept!):

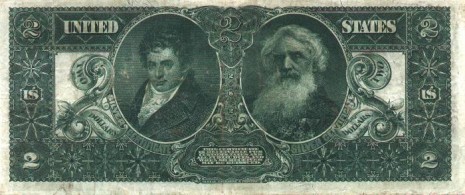

Here’s the back of the one-dollar bill. It shows George and Martha Washington (there’s a refreshing concept!): Here’s the two-dollar bill. The central figure is Science, and she is introducing Steam and Electricity (the two kids) to Commerce and Manufacture.

Here’s the two-dollar bill. The central figure is Science, and she is introducing Steam and Electricity (the two kids) to Commerce and Manufacture. On the back we see Robert Fulton (inventor of the steam engine) and Samuel Morse (inventor of the telegraph).

On the back we see Robert Fulton (inventor of the steam engine) and Samuel Morse (inventor of the telegraph).