Serialized radio dramas became popular in the 1930s. They were called soap operas, because they were sponsored by makers of cleaning products, among them P and G’s Oxydol, Palmolive Beauty Soap, and Colgate Tooth Powder.

Percolating Ideas and Brewing Revolutions

I’m at a Starbucks right now, sipping my double-tall-extra-hot-nonfat-latte, and thinking about the history of coffee. It arrived in Europe during the seventeenth century.

I’m at a Starbucks right now, sipping my double-tall-extra-hot-nonfat-latte, and thinking about the history of coffee. It arrived in Europe during the seventeenth century.

What did people drink before then? Like in Shakespeare’s day? Not water, if they could help it. In most towns and cities, water was foul-smelling, bad-tasting, and contaminated. It was used mostly for boiling up your dinner—meat if you were rich, vegetables if you were part of the other 99%. People didn’t drink a lot of milk. Without refrigeration and pasteurization, it spoiled quickly and made you sick, if you lived too far from the cow. Nor did they have the option of coffee (see above) or tea, which didn’t arrive in the west until the eighteenth century.

So most people drank alcohol. Every man, woman, and child averaged a gallon of wine or beer or ale or mead or similar every day, and they sloshed down flagons of the stuff at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Although usually not as strong as we might drink today, these beverages must have kept a good many people in a constant state of mild inebriation.

But that all changed when coffee made its way to the west by way of Arabia. The first coffee houses appeared in London in the mid-1600s, during Cromwell’s rule, and in Paris in the 1670s. In Paris, men and women could meet in public places and talk with total propriety, something previously unheard of.

But that all changed when coffee made its way to the west by way of Arabia. The first coffee houses appeared in London in the mid-1600s, during Cromwell’s rule, and in Paris in the 1670s. In Paris, men and women could meet in public places and talk with total propriety, something previously unheard of.

Between 1732 – 34, as coffee was rapidly gaining popularity in Germany, Johann Sebastian Bach composed a “Coffee Cantata.”

According to Tom Standage’s fascinating book, A History of the World in Six Glasses, coffee helped usher in a new rationalism and a flurry of intellectual activity known as the Scientific Revolution, culminating in the movement that came to be known as the Enlightenment. Coffee promoted sharpness and clarity of thought and was a safe alternative to alcoholic drinks, sobering rather than intoxicating. As Standage puts it, “Western Europe began to emerge from an alcoholic haze that had lasted for centuries.” It was “the ideal beverage, in short, for the Age of Reason.”

By 1750 there were 600 coffee houses in Paris. Revolution was brewing.

Ancient Game

The game Parcheesi (originally called Pachisi, which means 25 in Hindi) was first played in India and may have been invented as long ago as AD 300.

Dumb Decor

In 1497, Leonardo finished his fresco of The Last Supper on a wall in the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Around 1650, the monks decided they needed a new doorway into the refectory, so they carved one right into the fresco.

Bonfire of the Vanities

I don’t know why I should continue to be shocked that in this day and age, books are still being banned. Book banning (and burning) has a long and ignominious history.

As the Renaissance dawned, great thinkers began to consider what it means to be human, to prize individual accomplishments, and–most ominously, to members of the clergy–to question the absolute power of the church. And thanks to the invention of the printing press, more and more people gained access to books. Consequently, books, art, and sumptuous clothing became a target of spiritual reformers, specifically Franciscan and Dominican priests. These reformers preached that it was an act of piety and devotion to God to renounce your wealth, social position, and worldy goods.

Charismatic but extremely unfun preachers such as the Franciscan friar San Bernardino of Siena (1380 – 1444) and the Dominican priest Savonarola (1452 – 1498) staged “bonfires of the vanities,” huge fires in outdoor squares where people were encouraged to cast their wigs, fancy clothing, jewels, books, and artwork into the flames. Unfortunately, included among these frivolous items were priceless masterpieces by such artists as Boccaccio and Botticelli.

Royalty Payments

In 1398, Geoffrey Chaucer, writer of the Canterbury Tales, was granted 252 gallons of wine a year by King Edward III.

Death of Tchaikovsky

There’s a major mystery surrounding the death of the composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. According to most accounts, he died of cholera in 1893, after drinking a glass of unboiled tap water. Which would have been a reckless thing to do, because by 1893 everyone knew that cholera was a water-borne disease, and that it was tantamount to suicide to risk drinking unboiled water. Which is precisely the point. It certainly wasn’t accidental. So was it suicide? Or was he murdered? Did he even die of cholera, or was it a slow-acting poison that mimicked the symptoms of cholera? Arsenic certainly comes to mind; as I have blogged about before, it was a common poison precisely because its symptoms looked so much like cholera. Another, more recent theory, is a more prosaic one, that his doctor didn’t recognize the symptoms of cholera until too late. Maybe he didn’t knowingly drink a glass of unboiled water. Maybe he just got cholera in one of the many ways you can get cholera. A diseased fly could have landed in his borscht.

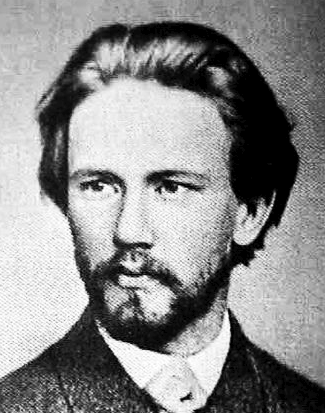

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky with his wife Antonina Miliukova during their honeymoon in 1877. The marriage lasted 9 days.

The true cause of his death will probably always be a mystery. Those who ascribe to the murder theory claim that Tchaikovsky may have been forced to drink the cholera/arsenic-laden water by a tribunal of noblemen to cover up his affair with a young duke. Those who ascribe to the suicide theory claim that he was despondent over the luke-warm reception of his most recent composition. Or that he was despondent and full of self-loathing about his homosexuality, and fearful of bringing shame upon his family. Sadly, as demonstrated in letter after letter, he regarded his homosexuality as “a terrible weakness and a shameful disease that ought to be curable.”* What’s not in debate is that he was a tortured man.

Sources:

“Tchaikovsky’s Death—the Riddle Endures,” Donal Henahan NYT 11/20/88

*“Did Tchaikovsky Really Commit Suicide?” Donal Henahan NYT 7/26/1981

“How did Tchaikovsky die?” Adam Sweeting The Telegraph 1/15/2007

Seven-Up for When You’re Down

The soft drink 7-Up was invented in1929, and was originally called “7 Up Lithiated Lemon Soda.” The origin of the name is unknown, but the soda did contain seven ingredients– including lithium, which is a mood stabilizing drug. The soda became wildly popular after the Wall Street Crash.

http://www.snopes.com/business/names/7up.asp

Faites ce que je dis . . .

Political philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778), who famously wrote about education and the general innocence of children, fathered five illegitimate children and consigned all of them to an orphanage.

Express Mail

My sixteen-year-old daughter will soon be getting her driver’s license. I’ve already experienced this anxiety-ridden time once, with her older brother. We parents know all the statistics about teenagers and risk taking. We know how dangerous driving is. To make matters worse, I’m a gasper. The older kid can’t stand when I sit in the passenger seat, because even though the kid has had his license for over two years, I still gasp at everything. (I blogged about risk-taking, fun-loving genetic predispositions here.)

Obviously, risk-taking teens are not a new phenomenon. Over a century and a half ago, teenage boys flocked to be part of the Pony Express system, a terribly dangerous job.

By 1860, thanks to the gold rush, almost half a million people were living in the western states. And they were eager to have the delivery time of their mail improved, which often took months to arrive.

So the call went out for cross-country riders–young, lightweight men under the age of eighteen–who were not only expert horsemen, but also willing to risk outlaws, hostile Indians, and bad weather. It was an extremely hazardous route. Orphans were preferred. About 80 teenagers were hired. They had to sign a pledge not to swear, drink alcohol, or fight.

So the call went out for cross-country riders–young, lightweight men under the age of eighteen–who were not only expert horsemen, but also willing to risk outlaws, hostile Indians, and bad weather. It was an extremely hazardous route. Orphans were preferred. About 80 teenagers were hired. They had to sign a pledge not to swear, drink alcohol, or fight.

The Pony Express consisted of relays ten miles apart, of men riding horses carrying saddlebags of mail across a 2000-mile trail. They covered about 250 miles in a day, and even rode throughout the night. The letters were wrapped in oiled silk to protect them from the elements. The price of sending a letter was $5, but it dropped to $1 per half-ounce. The first westbound trip was completed in just under ten days, which is pretty impressive when you consider how long it takes to drive across the country in a car. According to the Smithsonian’s National Postal System website, the arrival of the first rider into San Francisco, shortly before midnight on April 13th, 1860, was met with throngs of cheering people.

Despite the name, the riders rode horses, not ponies. But the horses were definitely small, chosen for their speed and stamina.

In October, 1861, the Pony Express was replaced by the telegraph system.