On this date in 1785, Frenchman Jean-Pierre Blanchard and American John Jeffries became the first humans to fly in a hot air balloon across the English Channel. To avoid falling into the sea, they had to dump everything they could overboard, including most of their clothing. The two freezing balloonists made it safely to the other side.

Howdy, Neighbor

Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” and Samuel Clemens, whose pen name was Mark Twain, were next door neighbors in Hartford, Connecticut.

Coffee Slushie

Honore de Balzac was unquestionably a caffeine addict. He consumed at least fifty cups of coffee a day in the form of pulverized roasted coffee with barely any water. Eventually, he took to eating ground coffee straight.

Call on Line One

Rutherford B. Hayes (president 1877 – 1881) had the first telephone installed in the White House. The White House was given the number “1.”

Suitable

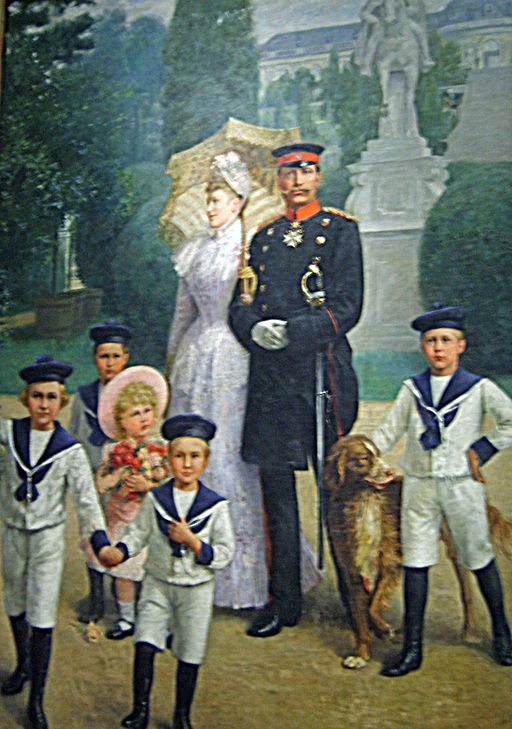

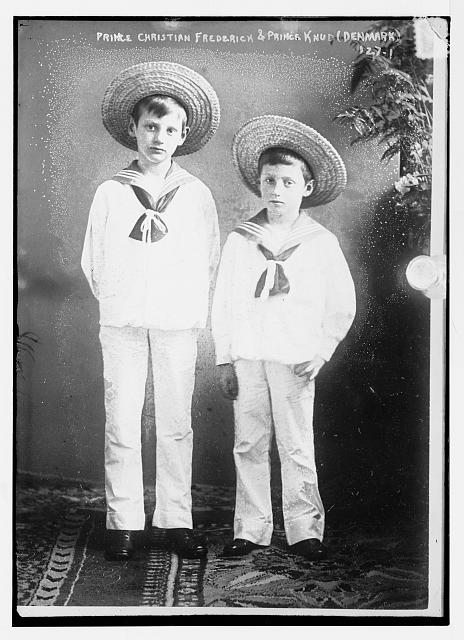

On Friday I wrote about some bizarre (to us) eighteenth-century children’s fashions. What became the dominant fashion for kids of the nineteenth century? Sailor suits. To look at photos and portraits of kids from that century, you’d be forgiven for wondering if platoons of kids had been conscripted into the navy, both in England and in America. According to the FIDM museum website, the style for sailor suits for kids was prompted by this picture of Prince Albert, painted in 1846.

According to that website, the British Royal Navy was a symbol of the United Kingdom’s colonial empire and position as a world power. “By dressing Albert Edward and her other sons in naval uniforms, Queen Victoria indicated her aspirations for her children and her country.” Children of royalty in other countries began wearing sailor suits modelled after their own navies, and eventually, the style made its way to the United States, and trickled down to everyday wear, for children of means at least. Sailor suits were appropriate for everything from fancy dress to school uniforms.

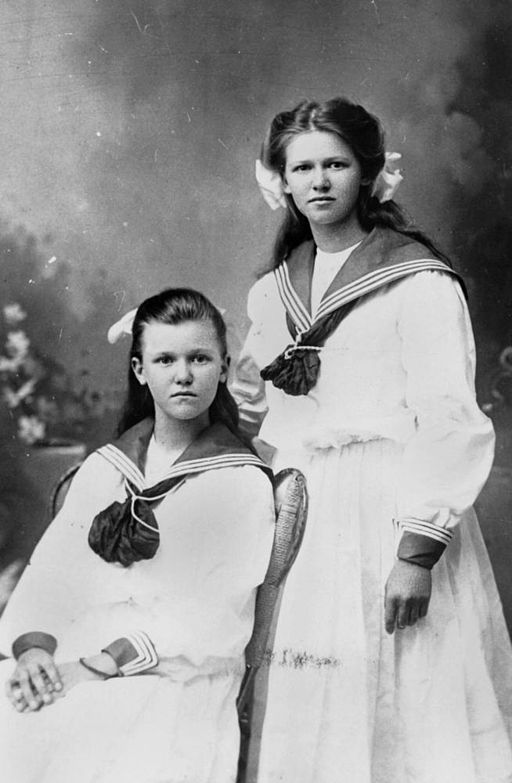

For formal wear (which is what most kids wore to be photographed), girls were still way behind boys in the comfort department. Girls’ corsets were not discarded until well into the 19thcentury. Fancy dress for girls included frills, lace and ruching, usually worn with thick wool stockings and side-buttoned, ankle-length boots (even in summer).

By the end of the nineteenth century, girls were finally permitted simpler, more practical “pinafore” dresses, often with aprons, although still with those thick black stockings, tightly-buttoned or lace-up boots—and woolen undergarments.

By the turn of the century, you start to see both girls and boys wearing sailor suits—navy blue wool in winter, white cotton in summer. Although this was a pre-zipper (these were patented in 1893 but didn’t trickle down to kids’ clothing for awhile), pre-Velcro, pre-stretch-fabric time, these clothes must have been a godsend for mothers or nursemaids. Imagine getting a kid dressed and undressed with all those multiple tiny buttons. Scroll down and have a look.

By the time of the first World War, children’s formal clothes were finally replaced by more practical garments, thanks largely to the fact that there were so many fewer servants available to help children get their clothes on and off.

By the time of the first World War, children’s formal clothes were finally replaced by more practical garments, thanks largely to the fact that there were so many fewer servants available to help children get their clothes on and off.

Make Way!

In 1865, the British government decreed that all self-propelled motor vehicles had to travel at walking speed and be preceded by a man waving a red flag. The law was not repealed until 1893.

Boys Will Be Boys, Eventually

On Fridays, my youngest son has to wear “formal dress” to school. This involves a jacket and tie, khakis, and real shoes rather than sneakers. He hates formal school dress day. The kid has no idea how easy he has it. I mean, look at poor Aleksey Bobrinsky up there in his tight suit and breeches, and his powdered wig. Admittedly, people wore their nicest finery to have their portraits painted, but even so–this must be his equivalent of formal school dress. (I wonder if my son would complain less if he were allowed to come to school with a rapier in his belt, like Aleksey’s.) Be that as it may: on Wednesday, I discussed what babies used to be made to wear. If you missed that post, it might be worth a look, to put this one in context. Today’s subject is what kids were made to wear.

If you’ve ever walked through a portrait gallery at a museum, you might be forgiven for assuming that all the portraits from the 18th century that feature children show only girls, and never boys. Every child seems to have on a frilly, flouncy dress and sport long, bouncing ringlets. And a corset. But take a closer look. Many of these children are, in fact, boys. You can sometimes tell by the shoes—boys’ heels tend to be a tad lower than those of girls.

I could show you dozens upon dozens of examples, but here are a few. To re-state: THESE ARE ALL BOYS:

Really, I could keep going, but I think you get the picture.

Girls would begin to be dressed in clothing much like their mother’s, from an early age, often as young as two. Most parents believed that a stiffened torso was essential to developing good posture, so both boys and girls were made to wear whaleboned bodices.

When a boy reached the age of six or seven he would at last discard his gown and be “breeched.”

The French writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau gets much of the credit for influencing the change in children’s dress during the latter part of the eighteenth century. He asserted that children’s physical and social needs should be considered as different from those of adults. Therefore, Rousseau argued, they should be allowed to wear plain, comfortable clothing. This was a radical concept for most people. “Skeleton suits” for boys appeared, so called because they fit loosely on the child’s frame. (As a side note: Rousseau, that Great Emancipator of children, fathered five kids with a woman he never married. He sent them all to the foundling hospital. Nice.)

A few examples of skeleton suits:

Ok, so it’s not exactly something a kid might wear to go outside and shoot hoops, but it’s certainly an improvement.

Still, boy-skirts didn’t entirely go away. Here’s a picture of Franklin Delano Roosevelt at age 3 (in 1885).

If the Shoe Fit

George Washington wore a size 13 shoe.

A Strain on the Conversation

During one of his frequent bouts of dementia, King George III of England insisted on ending every sentence with the word “peacock.”

How They Rolled

I went to a baby shower a couple of weeks ago, and was amazed at all the adorable and functional baby clothing they make these days. Babies today are pretty lucky, considering what they used to be forced to wear.

In seventeenth century Europe and America, babies started out life swaddled (tightly wrapped). The seventeenth-century infant would be dressed in a shirt and “tailclout” (an early word for a diaper, cloth of course), and then bandages would be wound in a spiraling fashion the entire length of the baby’s body. On his or her head was a biggin (a cloth cap). The poor, immobilized child might be unwound a couple of times a day to allow it to move its limbs and to be cleaned, but otherwise that’s the way the baby spent the first four to six weeks of its life. People believed swaddling would give the child a straighter back and limbs.

When at last the swaddling came off, the child was “short-coated,” meaning it was dressed in a long, loose gown that reached to the feet. If you’ve ever watched a baby learning to walk, imagine adding a floor-length dress to his challenge. Toddlers could be kept out of trouble and away from blazing hearths by sewing “leading strings” to their clothing. The mother would hold onto one end, in order to yank a child away from dangerous things like the blazing hearth, while she went about her dozens of tasks. On its head the child wore a “pudding cap,” which was an early incarnation of a crash helmet, with a rolled piece of fabric acting as padding if the kid fell down. Since safety pins hadn’t yet been invented, baby diapers, made of linen or rags, were secured with straight pins.

You can see a pretty good example of a pudding cap and leading string in the portrait, above, by Peter Paul Rubens. It’s the artist, his wife, and one of their five children.

Oh and by the way. The kid in the picture? It’s a boy. And it looks as though he’s wearing a corset. We’ll talk about that on Friday.