I saw the show Hamilton last week. My family is somewhat obsessed with it, and we knew every note of the soundtrack. Still, it exceeded our expectations.

I saw the show Hamilton last week. My family is somewhat obsessed with it, and we knew every note of the soundtrack. Still, it exceeded our expectations.

One question left unanswered by the musical is: what became of Alexander Hamilton’s killer, Aaron Burr? Why was he not arrested for murder?

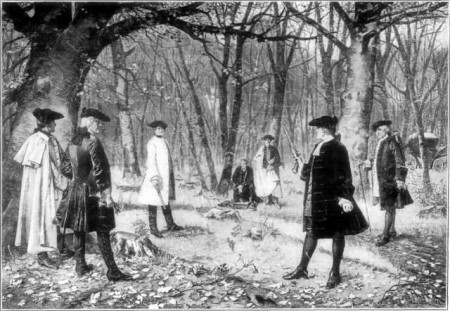

Quick summary: Burr, the Vice President under Thomas Jefferson, challenged Hamilton to a duel, after years of simmering tensions and mutual badmouthing of one another in the press. On July 11th, 1804, Burr shot Hamilton, and by the afternoon of the following day, Hamilton was dead.

The duel had been fought in New Jersey, where dueling was legal. Still, there was a movement to have Burr arrested for murder in both New York and New Jersey. Dueling was a misdemeanor, but murder was a felony. Burr temporarily fled to Georgia, but in November, he returned to Washington to complete his vice-presidential term.

He then moved west, became embroiled in a conspiracy to seize some western territories, was arrested for treason, and acquitted. Whatever was left of his reputation was now destroyed. He left for exile in England, and lived there until 1812. He returned to New York, practiced law in relative obscurity, and died in 1836 at the age of eighty.

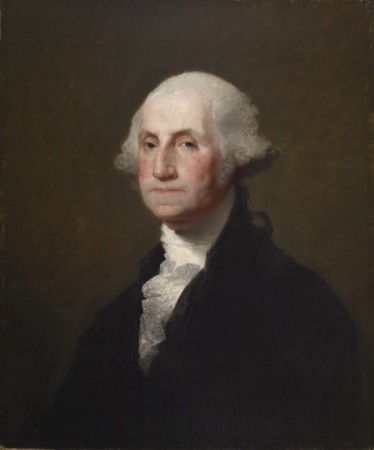

At the time of the Burr-Hamilton incident, dueling as a way to resolve grievances and defend one’s honor had become unfashionable in the North. Both George Washington and Benjamin Franklin had condemned the practice. It was still common in the South. But even in places where it was illegal, lawmakers tended not to enforce punishments for duelists. It wasn’t until the Civil War that dueling went completely out of fashion, even in the South.

Happy Saint Patrick’s Day! While not Irish myself, I do have quite a few Irish relatives by marriage on my Italian mother’s side. (“They meet each other in church!” as my Irish uncle-by-marriage once cheerfully explained to me.) To honor the day, I thought I’d share five fascinating facts about Ireland’s patron saint, Patrick (approximately CE 389 to 461). March 17th is believed to be his death date.

Happy Saint Patrick’s Day! While not Irish myself, I do have quite a few Irish relatives by marriage on my Italian mother’s side. (“They meet each other in church!” as my Irish uncle-by-marriage once cheerfully explained to me.) To honor the day, I thought I’d share five fascinating facts about Ireland’s patron saint, Patrick (approximately CE 389 to 461). March 17th is believed to be his death date.

![Jean-Antoine Houdon [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sarahalbeebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Christoph_Willibard_Gluck_by_Jean-Antoine_Houdon-338x450.jpg)