Poor Richard.

Poor Richard.

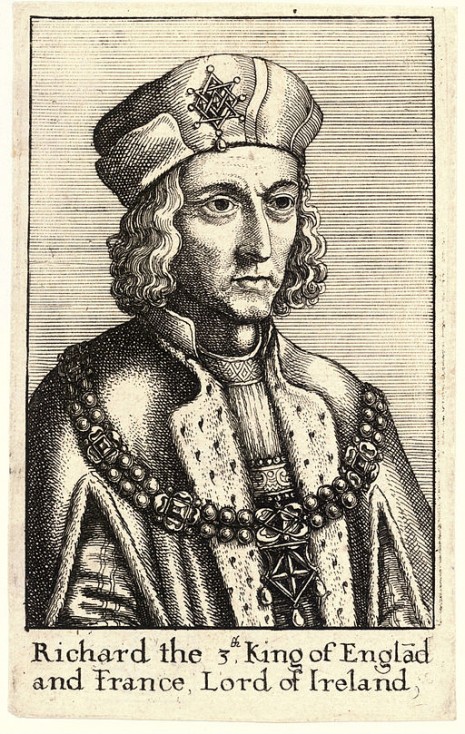

Richard III, I mean, the last of the Plantagenet kings (1452 – 1485). He’s the one who’s been very much in the news lately, because they found his remains beneath a car park in Leicester, England.

He also has a terrible reputation. He’s the guy Shakespeare called a “poisonous bunch-backed toad,” and “that foul defacer of God’s handiwork,” and who was said to have murdered his two little nephews in the Tower in a bloody ascension to the throne. I blogged about him here.

Now the latest news is that not only was he “one of England’s most despised monarchs,” he also had—brace yourself—intestinal parasites.

My brother, Luke, sent me this article about foot-long roundworms. His email subject line was lovingly entitled: “This reminded me of you.” (I get such emails and links a lot from my friends and family. Anything gross or poop- or infectious-disease related. Which makes me happy—please keep ‘em coming, friends and family.)

The article says that archaeologists found roundworm eggs in the soil around his pelvis, near where his intestines would have been. Say or think what you will about RIII, but the fact that he was afflicted with intestinal worms is not all that shocking. Pretty much everyone had them, before antibiotics became part of the arsenal of modern living. In fact, although no one thinks it’s good to have worms, many legit scientists believe that our lack of parasites nowadays has caused our immune systems to go haywire, and may be a major factor in why autoimmune problems, including allergies and asthma, are so rampant in modern western societies.

(You can read more about parasitic worms in my upcoming book, coming out next year. See what you have to look forward to?)

I work at home, and despite being on the ‘do not call’ list, I get a lot of telemarketing calls. I have found myself thinking that it must have been so much easier in the good old days, before telephones—and texts—were a constant source of interruption. But actually, the recent past may have been just as bad, in a different way.

I work at home, and despite being on the ‘do not call’ list, I get a lot of telemarketing calls. I have found myself thinking that it must have been so much easier in the good old days, before telephones—and texts—were a constant source of interruption. But actually, the recent past may have been just as bad, in a different way.

I’ve

I’ve  According to the book I’ve been reading,

According to the book I’ve been reading,