Karl Marx so loathed bad reviews that he threatened to challenge his bad reviewers to a duel. Luckily for him, he never followed up on his threat–he was severely near-sighted.

The Name Game

How did our country get named “America?”

Most sources agree that “America” is a feminized version of Amerigo, after the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci (1454? – 1512). But it’s unlikely Vespucci ever set foot in modern-day North America, nor did he actually captain any voyages to the New World. He went as an observer. So how did America get named after him?

In 1507, a mapmaker named Martin Waldseemüller made a huge map that was meant to update Ptolemy’s map (the one used by Columbus, which grossly underestimated the size and circumference of the Earth). The new map added newfound knowledge of a fourth continent (North/South America), hitherto unknown to Europeans, along with a new (to Europeans) ocean, called the Pacific. The map included data from one of Vespucci’s voyages to the New World (probably the one from 1501-2). Waldseemüller called it (in translation) Universal Geography according to the Tradition of Ptolemy and Contributions of Amerigo Vespucci and Others. He labeled what is modern-day Brazil “America,” after Amerigo, and put Ptolemy in one corner and Vespucci in another.

Six years after the 1507 map was published, Waldseemüller tried to recant his original Vespucci attribution and to rename the continent of South America “Prisilia” and North America terra de Cuba, Asiae partis. According to historian Felipe Fernandez-Armesto in his book, Amerigo, Waldseemüller swung the other way and accepted Columbus’s bizarre claim that Cuba was part of Asia.* But Terra de Cuba, Asiae Partis didn’t roll off the tongue as easily, so the name “America” stuck. By 1538 another mapmaker labeled both the Northern and Southern halves “America.”

A lot of controversy surrounds Vespucci’s voyages. For starters, no one is entirely sure if he travelled to the New World two times or four times. Some letters originally thought to be written by Vespucci surfaced which are now believed to be inauthentic.

Vespucci was from Florence, and began his career as a sort of dodgy businessman who worked for the Medici family as, among other things, a wine merchant, jeweler, debt collector, and pimp (or a “procurer” as it was euphemistically called).** He eventually moved to Seville, Spain, at just about the same time that Christopher Columbus was drumming up backers for his trip across the Atlantic. Amerigo helped provision Columbus’s ships, which earned him Ralph Waldo Emerson’s disparaging nickname, “pickle dealer.” Eventually he decided he’d garner more fame and fortune actually embarking on these voyages, rather than just provisioning them.

Many Columbus fans thought Vespucci had taken credit away from Columbus, and that the new continent ought to have been named after the great admiral instead. But the real outrage is that no European ought to be credited for discovering the “New World.” It had long been inhabited by native people at the time of Columbus’s arrival. And there is compelling evidence that the late fifteenth century voyages of Columbus and Vespucci were not the first time explorers from the Old World had come to the New World. The Vikings probably sailed to Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and possibly as far south as Cape Cod in AD 600, and much earlier than that, there is evidence that West Africans and/or Phoenicians sailed to Central America—perhaps as long ago as 1000 BC. The nine-foot Olmec Heads in southeastern Mexico have distinctly African features and have led to much speculation by archaeologists that an ancient civilization from Africa was the first to cross the Atlantic.***

* Fernandez-Armesto, 187

**Fernandez-Armesto, 35

***James W. Loewen, 43-4

Heart and Soul

The physician and theologian Michael Servetus (Miguel Serveto in Spanish) 1509? – 1553 was the first European to accurately describe pulmonary circulation. He was condemned as a heretic and burned at the stake by John Calvin and his followers, along with his books.

Twin Peaks

I’ve blogged before about the outrageous headgear worn by well-dressed European women starting around 1380 or so, and reaching its peak (so to speak) around the 1430s. Towering peaked, ram-horned, or heart-shaped headdresses, often draped with veils, became all the rage. They were called hennins (the one-horned version) and escoffions (the two-horned version) and, in England, “steeple headdresses.” Sometimes the horns could be a yard long.

What I didn’t realize, until I read Accessories of Dress by Katherine Lester and Bess Viola Oerke, was how much these headdresses were despised by the older or more pious sorts. I guess fourteenth century parents of teenagers were as horrified by hennins as modern parents are by So Lows and tattoos. Preachers and moralists urged people to protest these outrageous fashions by shouting “War to the hennin!” and “Beware the ram!” whenever a woman approached them wearing the offending item. (18)

What I didn’t realize, until I read Accessories of Dress by Katherine Lester and Bess Viola Oerke, was how much these headdresses were despised by the older or more pious sorts. I guess fourteenth century parents of teenagers were as horrified by hennins as modern parents are by So Lows and tattoos. Preachers and moralists urged people to protest these outrageous fashions by shouting “War to the hennin!” and “Beware the ram!” whenever a woman approached them wearing the offending item. (18)

Speaking as the mother of three teenagers, I’m pretty sure this didn’t work.

And just imagine the battles fought between parents and their teenaged boys who sported tunics like these:

Girls and Curls

The first stanza of the poem that begins “There was a little girl, /Who had a little curl,/right in the middle of her forehead…” has been attributed to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Sidney Kramer, “There Was A Little Girl,” (287)

Yellow-Fruit Fever

Before it was proven that a mosquito was the vector of yellow fever, people believed the disease was spread by the wind, or by yellow fruit. Crates of oranges and bananas were buried during epidemics.

Great Medical Disasters, Page 15

I See Muslin, I See France, Finally Some Underpants

Happy New Year everyone!

I’m back at my desk after lots of holiday revels, research trips, and long hours of book revisions. While in DC last weekend I went to the National Gallery in DC. It’s a pretty incredible place to go if you happen to be writing a book about fashion history. Being me, I have been doing an in-depth study of underwear, so it was fun to stumble upon this painting, attributed to the “Circle of Jacques-Louis David,” and dated 1798—that would be five years after Marie Antoinette was executed, and one year before Napoleon appointed himself “First Consul,” a.k.a dictator, and began taking over the world.

Members of the nobility who’d survived the Revolution hastily de-corsetted and de-hooped themselves and adopted a simple, classical style based on ancient Greece. It probably won’t shock you to learn–based on the above painting–that during this period of Regency and Empire fashion, the bustline became a big focus. (“Bust improvers” enjoyed a thriving business. They were made of wax or stuffed cloth.)

Members of the nobility who’d survived the Revolution hastily de-corsetted and de-hooped themselves and adopted a simple, classical style based on ancient Greece. It probably won’t shock you to learn–based on the above painting–that during this period of Regency and Empire fashion, the bustline became a big focus. (“Bust improvers” enjoyed a thriving business. They were made of wax or stuffed cloth.)

But here’s what might shock you: it was under these thin, muslin, diaphanous dresses that for the first time ever, women began wearing underwear—by which I mean knee- or ankle-length drawers. I actually don’t think this woman is wearing any, or at least, so far as I could tell by looking at it as closely as I could without alarming the museum security guard. But according to Emily Ewing’s book Dress and Undress: A History of Women’s Underwear, it was not until this point–around the turn of the eighteenth to nineteenth century–that women stopped going commando–i.e., wearing just smocks, stays and petticoats. (If you want to know how women managed going to the bathroom in those huge panniers and hoops of the prior century, you’ll just have to read my book.)

The new style of dress for women in post-Revolutionary France emulated the fashions of the ancient Greeks, whom the French admired as the first Republic. Because people mistakenly believed that the white marble of the Greek statuary was as it had been created, most of these neoclassical style dresses were white. People didn’t realize that many of the original Greek statues had been painted in bright colors (and therefore probably the clothing had been brightly colored, too.) (Ewing 54-6)

Stories circulated that some of the more daring women wore nothing but a flimsy chemise underneath their thin muslin dresses and even misted themselves with water so that their dampened dresses clung, wet-t-shirt-style, to their bodies, but that’s unsubstantiated.

Even if it wasn’t dampened, imagine wearing this kind of dress on a cold January day, before the invention of central heating. Rates of flu and pneumonia supposedly skyrocketed. After one particularly virulent influenza epidemic carried off scores of victims, flu became known as the “muslin disease.”

Merry Christmas

The phrase “Merry Christmas” was not widely used until Dickens popularized it in A Christmas Carol, published in 1843.

thanks to:

http://interestingliterature.com/2013/12/17

/dickensachristmascarolat170/

Boys Will Be Girls

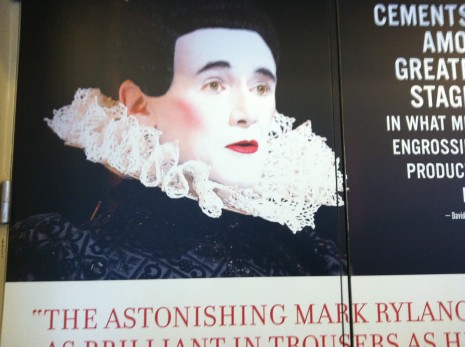

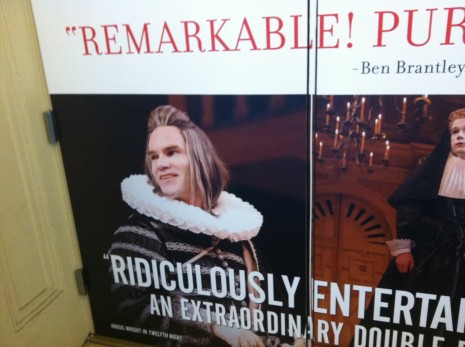

This past Wednesday, I went to see Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night on Broadway.

This past Wednesday, I went to see Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night on Broadway.

It starred some incredible actors (an all male cast) in period dress, which is cool in and of itself, but the coolest thing about it, for me, was the fact that you could go to the theater early and watch the actors getting dressed (by dressers) right on the stage. I went with my daughter, who was a very good sport about arriving ultra early, and even though we had seats that were pretty far back, a nice usher let me come up before the show and stand right up at the front, with my elbows on the stage, to watch the actors get dressed up close. My daughter was somewhat mortified by this, but she’s used to having a peculiar mother.

It starred some incredible actors (an all male cast) in period dress, which is cool in and of itself, but the coolest thing about it, for me, was the fact that you could go to the theater early and watch the actors getting dressed (by dressers) right on the stage. I went with my daughter, who was a very good sport about arriving ultra early, and even though we had seats that were pretty far back, a nice usher let me come up before the show and stand right up at the front, with my elbows on the stage, to watch the actors get dressed up close. My daughter was somewhat mortified by this, but she’s used to having a peculiar mother.

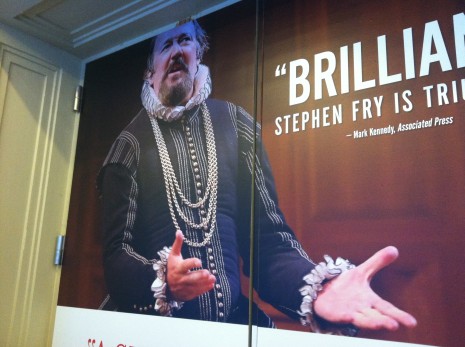

About one foot away from me, close enough to touch his kirtle, was the actor Paul Chahidi, who plays Maria, the witty maid who writes the trick letter to Malvolio, played by the peascod-belly-wearing Stephen Fry. (Side note: I’ve been a fan of Stephen Fry ever since he played Jeeves to Hugh Laurie’s Bertie.)

We weren’t allowed to take pictures, so I stood and sketched the layers as they put them on Maria–chemise, bodices and petticoat, bum roll, gown, neck and wrist cuffs and half-ruff, silk stockings and garters and shoes. And pins, pins, pins. (Mark Rylance, playing the Countess, also wore a border–amusing border story here.)

Mr. Chahidi was gracious and lovely and chit-chatted with me the whole time. It was slightly disconcerting to see him before they put his wig on (he’s, um, bald)—his face was porcelain white with daubs of red on each cheek. (I’m pretty sure they didn’t use liquid lead.) While his stays were being laced up he asked me what I was sketching and I told him I was working on a book about history and fashion for kids and he smiled and said that was “brilliant.” He hitched his breath between the syllables, though, as his dresser was just cinching in his stays. So it came out as “Brih-gasp-li-ant.”

And then the play was brilliant.

We were allowed to take pictures at the very end, so here’s a blurry one where you can kind of see what they wore.

Stay in School

In Puritan New England, celebrating Christmas was frowned upon. Boston public schools remained in session on December 25th as late as 1870.