I subscribe to the diary of Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703–and his name rhymes with ‘cheeps”), and from time to time on this blog I like to check in with him. He kept his diary during what turned out to be (arguably) nine of the most exciting years of British history—from 1660 to 1669. Over the course of those nine years, Pepys records eyewitness accounts of major events that include the restoration of Charles II to the throne, the plague of 1665, and the great fire of London of 1666.

I subscribe to the diary of Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703–and his name rhymes with ‘cheeps”), and from time to time on this blog I like to check in with him. He kept his diary during what turned out to be (arguably) nine of the most exciting years of British history—from 1660 to 1669. Over the course of those nine years, Pepys records eyewitness accounts of major events that include the restoration of Charles II to the throne, the plague of 1665, and the great fire of London of 1666.

I have grown very fond of Sam, flawed and vain as he is, and look forward to the daily entry that arrives in my inbox every evening.

In his entry on 19 January 1660, he matter-of-factly throws out this sentence:

To the Comptroller’s, and with him by coach to White Hall; in our way meeting Venner and Pritchard upon a sledge, who with two more Fifth Monarchy men were hanged to-day, and the two first drawn and quartered.

We’ll leave aside the fact that witnessing a public execution would be taken in stride during the normal course of one’s seventeenth century day, and examine who the two unfortunate souls on the sledge were.

At the time Sam wrote this entry, Cromwell’s protectorate was dead and Charles II had assumed the throne. Pretty much everyone who valued their lives and their livelihood—including Sam—became a royalist, no matter what their politics had been during the Cromwell era. Venner and Pritchard were executed as traitors—the “Fifth Kingdom” was a group of religious zealots, which is saying something in the seventeenth century, end-of-the-world-is-coming types who were anti-government in any form. They’d first tried to overthrow Cromwell in 1657 and then tried to prevent the restoration of Charles II.

So maybe you’re wondering why these two fairly obscure unfortunates are even worth a mention. Well just a few months before this execution, the poet John Milton had also been thrown into prison. And he was in serious peril, because he had supported the Commonwealth and had written fairly inflammatory anti-royal pamphlets. Luckily he had friends in high places, and they protected him from being executed. He was released after a few months. But it’s still shocking to think he could have met a fate similar to that of Venner and Pritchard, and that Paradise Lost might never have been written.

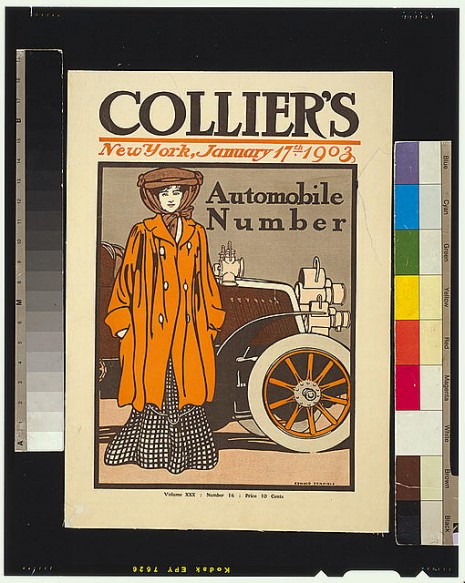

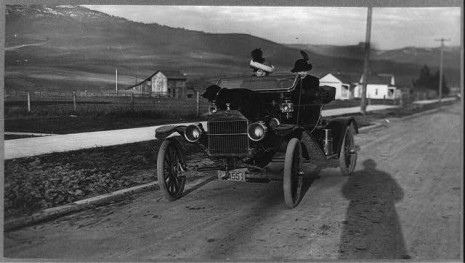

The automobile changed fashion quickly and dramatically. The first models were open to the air, so passengers wore goggles and “dusters,” and women often wore big, sweeping, net veils over their hats and faces. After all, the first roadsters reached perilous speeds of up to twenty miles an hour.

The automobile changed fashion quickly and dramatically. The first models were open to the air, so passengers wore goggles and “dusters,” and women often wore big, sweeping, net veils over their hats and faces. After all, the first roadsters reached perilous speeds of up to twenty miles an hour.

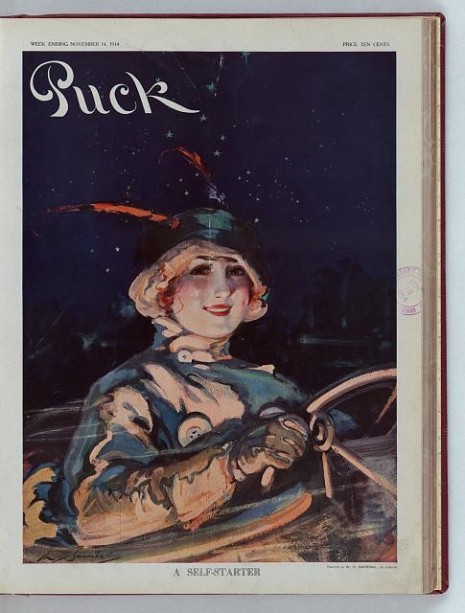

As motoring grew more popular, women cast aside their huge, floppy hats and cut their hair short. Close-fitting cloches didn’t fly off as easily. A few more early pictures:

As motoring grew more popular, women cast aside their huge, floppy hats and cut their hair short. Close-fitting cloches didn’t fly off as easily. A few more early pictures:

I’ve been reading about hydrophobia, or rabies. Before Pasteur developed his vaccine in 1885, there was no known cure. But lots of methods were tried.

I’ve been reading about hydrophobia, or rabies. Before Pasteur developed his vaccine in 1885, there was no known cure. But lots of methods were tried.