I’m in France for ten days with my history-teacher husband. On the itinerary are many places we’re both eager to see, including Lyon, some chateaux in the Loire Valley, the Bayeux tapestry, and the beaches and battle sites of Normandy. But Saturday was a special day for me. We visited the Paris sewers.

Yes, there is actually a museum devoted to exploring the sewers beneath the streets, of which Parisians get to be very proud. If you’ve read my Poop book, you’ll know that London was the first major city to build massive sewers, thanks to Sir Joseph Bazalgette. But Paris followed suit just a few years later. In 1854, Eugene Belgrand was appointed to be head of the Parisian Water Board.

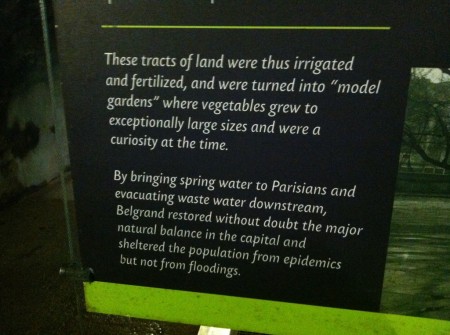

Yes, there is actually a museum devoted to exploring the sewers beneath the streets, of which Parisians get to be very proud. If you’ve read my Poop book, you’ll know that London was the first major city to build massive sewers, thanks to Sir Joseph Bazalgette. But Paris followed suit just a few years later. In 1854, Eugene Belgrand was appointed to be head of the Parisian Water Board.  His brilliant idea was to build aqueducts that supplied drinking water drawn from up river. His plan was completed in 1894, but not before Paris experienced serious cholera outbreaks as well as a major Big Stink, similar to the one in London in the 1850s. Interestingly, there’s no mention of the Paris Big Stink in the museum exhibit. But they have models of dredger wagons, which were used to move the euphemistically called “hybrid mixture” along and which then “irrigated and fertilized” fields downstream from the river. I’ve always felt sorry for those residents living downstream from these major urban engineering projects.

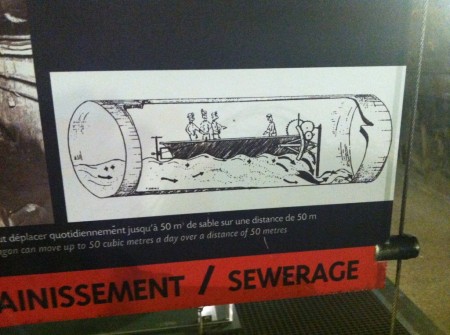

His brilliant idea was to build aqueducts that supplied drinking water drawn from up river. His plan was completed in 1894, but not before Paris experienced serious cholera outbreaks as well as a major Big Stink, similar to the one in London in the 1850s. Interestingly, there’s no mention of the Paris Big Stink in the museum exhibit. But they have models of dredger wagons, which were used to move the euphemistically called “hybrid mixture” along and which then “irrigated and fertilized” fields downstream from the river. I’ve always felt sorry for those residents living downstream from these major urban engineering projects.

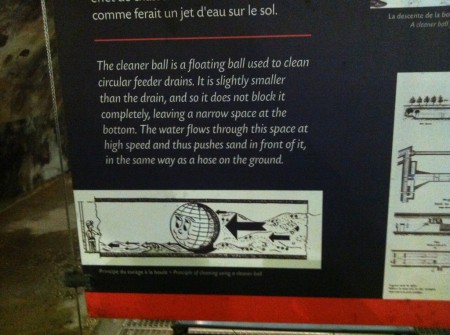

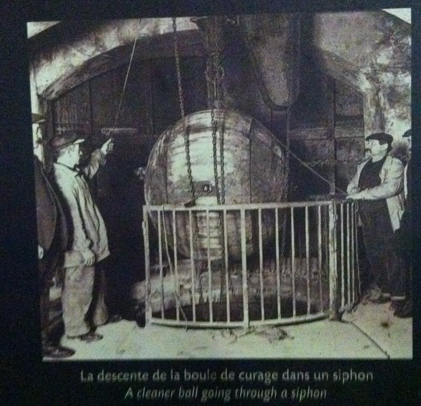

I learned about the so-called “cleaner balls” that are used to clean the sewers. They’re these giant floating balls that are slightly smaller than the tunnel’s circumference—the waste water is pushed through it around the ball at high speed. Here’s a picture. (The French, I’ve found, like to put cheerful faces on a lot of their signage.)

You can actually stand on grated flooring and watch the water whoosh by you as you make your way through the exhibit. Yes, it was a little sulphurous smelling down there, but I can’t begin to tell you how cool it was. Here’s a five-second video: IMG_2706My husband, I noticed, kept well away from the open grates. It was mostly me and the ten year old boys who ventured over them.

More than you want to know? All right, I’ll switch to open sewers channels in the streets.

We were walking through a lovely medieval district called Le Marais, which is also known as the Jewish quarter. I had to snap a picture of this narrow, cobbled street, which still has an open channel running through it the way it must have four hundred years ago.

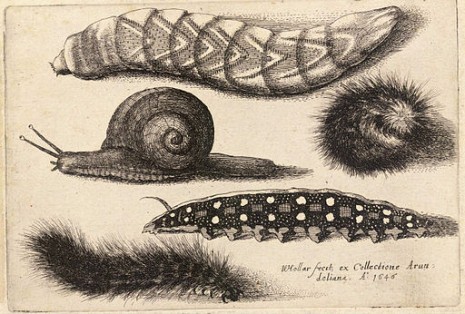

This is hardly breaking news—in fact, the Greek physician Hippocrates (460 – 370 BC) was the first to herald the benefits, but did you know that snail-slime face cream is a hot beauty trend? Creams containing slug mucus have been flying off the shelves in far-flung places like Korea and South America.

This is hardly breaking news—in fact, the Greek physician Hippocrates (460 – 370 BC) was the first to herald the benefits, but did you know that snail-slime face cream is a hot beauty trend? Creams containing slug mucus have been flying off the shelves in far-flung places like Korea and South America. Here’s a close-up. Snail slime was meant to represent sin. What a long way snails have come in the way of positive PR.

Here’s a close-up. Snail slime was meant to represent sin. What a long way snails have come in the way of positive PR.

Britain had to stop transporting convicts to the American colonies when the Revolutionary War began. In Britain, the big backlog of convicts was temporarily eased by allowing convicts who were eager to escape the hangman to enlist as soldiers.

Britain had to stop transporting convicts to the American colonies when the Revolutionary War began. In Britain, the big backlog of convicts was temporarily eased by allowing convicts who were eager to escape the hangman to enlist as soldiers.

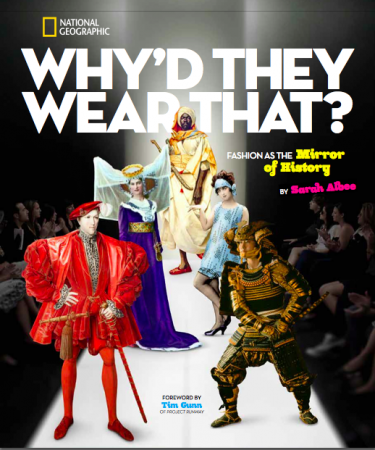

So what do you think? This is my first time working with Nat Geo, and they’ve been awesome, but perhaps because it’s Nat Geo, about a billion people have had to weigh in with opinions about the cover, way more than I’ve been accustomed to with my other books. And this final version was not completely what I had imagined the cover would look like. But the more I’ve looked at it, the more I’ve appreciated how much my opinion was listened to. I wanted it to say “history,” because the book is history-through-fashion (as opposed to the history of fashion). I asked for a mix of genders, for the inclusion of people of color, and that women not pose in coquettish poses. And they listened. So I’m happy. I’d love to hear what you think!

So what do you think? This is my first time working with Nat Geo, and they’ve been awesome, but perhaps because it’s Nat Geo, about a billion people have had to weigh in with opinions about the cover, way more than I’ve been accustomed to with my other books. And this final version was not completely what I had imagined the cover would look like. But the more I’ve looked at it, the more I’ve appreciated how much my opinion was listened to. I wanted it to say “history,” because the book is history-through-fashion (as opposed to the history of fashion). I asked for a mix of genders, for the inclusion of people of color, and that women not pose in coquettish poses. And they listened. So I’m happy. I’d love to hear what you think!

When many people think of galley slaves, poor wretches toiling away at their oars in dark, stinking ships, they might conjure up images from the movie Ben Hur and ancient Rome. But in fact, the Romans tended not to use slaves to man the oars of their battleships. It was the seventeenth century that was known as “the great age of the galleys.”

When many people think of galley slaves, poor wretches toiling away at their oars in dark, stinking ships, they might conjure up images from the movie Ben Hur and ancient Rome. But in fact, the Romans tended not to use slaves to man the oars of their battleships. It was the seventeenth century that was known as “the great age of the galleys.” When in 1685 Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes—a law passed by his grandfather Henri IV that had ensured the freedom of Protestant worship in France—many French Protestants (known as Huguenots) who tried to flee the country were sent to the galleys.

When in 1685 Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes—a law passed by his grandfather Henri IV that had ensured the freedom of Protestant worship in France—many French Protestants (known as Huguenots) who tried to flee the country were sent to the galleys. What was life like as a galley slave? We know something about it from letters and memoirs of Huguenot convicts.

What was life like as a galley slave? We know something about it from letters and memoirs of Huguenot convicts. After a long and often grueling march to the ports, the convicts would be sorted into groups of five—these would become the people with whom one would eat, sleep, and work, often until one died of old age or overwork or both. Each group of five men manned an eighteen-foot oar–and there might be fifty oars on a ship. The convicts remained chained to their places. With each stroke, they had to rise together and push the oar forward, and then dip it in the water and pull backward, dropping into a sitting position. During the heat of battle, rowers might be required to maintain full speed for twenty-four hours straight, and be fed biscuits soaked in wine without pausing in their exertions. Those who died—or lost consciousness—were cut from their places and thrown overboard.

After a long and often grueling march to the ports, the convicts would be sorted into groups of five—these would become the people with whom one would eat, sleep, and work, often until one died of old age or overwork or both. Each group of five men manned an eighteen-foot oar–and there might be fifty oars on a ship. The convicts remained chained to their places. With each stroke, they had to rise together and push the oar forward, and then dip it in the water and pull backward, dropping into a sitting position. During the heat of battle, rowers might be required to maintain full speed for twenty-four hours straight, and be fed biscuits soaked in wine without pausing in their exertions. Those who died—or lost consciousness—were cut from their places and thrown overboard.