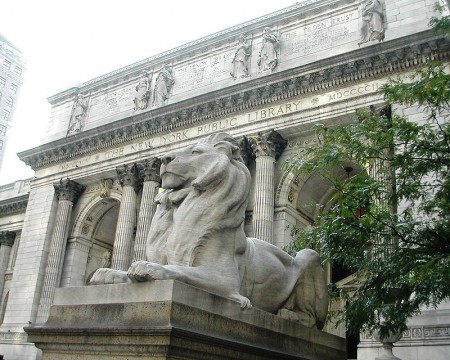

I have a new favorite publication. During my recent week of research in New York City, I spent many happy hours poring over nineteenth century copies of The British Medical Journal. I found it so diverting—literally—that it was difficult to stay focused on my area of research. It’s written in a very approachable, conversational style, well, for a medical journal—with lots of first-hand accounts from doctors about their ailing patients. And you find yourself filling in the human details between the lines.

For instance, in the correspondence section of the July 12, 1862 issue, there’s a lively dialogue between those in favor of sending people home with poisons in bottles marked with a “difference in shape and mode of pouring” and those who think it’s a dumb idea. Why sure, the first camp argues, it’s better to package the poison in a specially shaped bottle, so that when Mother sends seven-year-old Suzy to the corner store to collect a half pound of sugar for the trifle and a half pound of arsenic to kill the rats, Suzy will have a fighting chance not to get the two identical substances confused as she carries the packages home all jumbled up in her little white apron. The other camp thinks it’s the person’s own fault if he doesn’t bother to look carefully. As one Mr. Squire at the Pharmaceutical Society put it, “Such a person deserves to be poisoned.”

Then there’s the article entitled “Loss of an Eye from the Bite of a Leech” (May 31, 1862), where a doctor named Mr. Von Graefe (they weren’t called “Dr.” then) recounts that his patient, a five year old child, “had on account of headache been ordered a leech to the right temple.” The leech ended up crawling over to her eye, resulting in, well, just imagine. “Where were the parents?” I almost shouted. Why did no one realize the stupid leech had crawled to her eye? They don’t move that quickly! And why is Mr./Dr. Von Graefe publishing this story of his own ridiculous incompetence? These were the heady days before malpractice.

I could keep going and going. In the 6/14/1879 issue, a doctor describes how a guy purchased a doll for his one-year-old. The baby put the doll in her mouth and fell gravely ill. Turns out, the doll had a long green dress that was loaded with arsenic.

I’ll end with an article not from the BMJ but from my second-favorite publication, The Lancet (4/27/1861). A Mr. Skey recounts three patients of his, girls aged 15, 16, and 17, whom he treated for “enlarged bursae over the knee.” Touchingly, he dubs this malady “Housemaid’s Knee,” because it was “brought on by kneeling on a hard floor or stone steps whilst following their occupation as servants.” I think Mr. Skey might have been secretly hoping his name for this affliction might gain rapid popularity and perhaps accord him, in turn, some name recognition, but I don’t think the name stuck.

Update: As you’ll see in the comments, my English friend, Annabel, says that Housemaid’s Knee is still a familiar and recognized condition in the U.K. Perhaps Mr. Skey wasn’t even the originator of the name. I’ll have to go do some more research. Thanks, Annabel!!

The subject of today’s hilarity will be nicknames from the Viking Age. (

The subject of today’s hilarity will be nicknames from the Viking Age. (

![Ra-smit [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sarahalbeebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/512px-Chateau_de_Chenonceau_2008E-1-450x241.jpg)

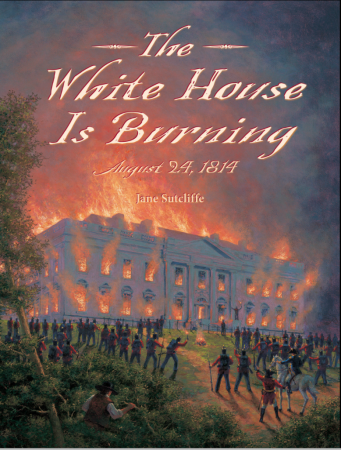

Today on the blog, please welcome my special guest: kidlit writer-friend, Jane Sutcliffe. Jane and I met through the New England chapter of SCBWI, and she is the author of over two dozen nonfiction books for kids, including the fantastic, recent picture book

Today on the blog, please welcome my special guest: kidlit writer-friend, Jane Sutcliffe. Jane and I met through the New England chapter of SCBWI, and she is the author of over two dozen nonfiction books for kids, including the fantastic, recent picture book