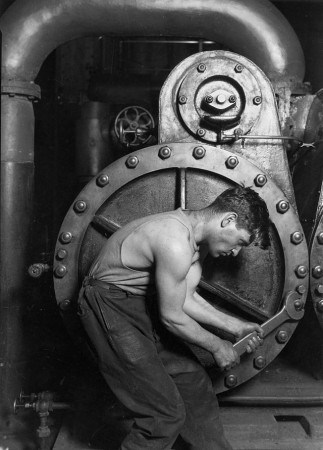

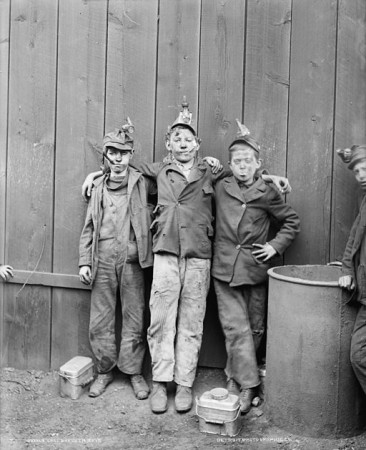

Nowadays you don’t generally know what someone does for a living based on how she walks or dresses, unless it’s a firefighter in uniform, or a police officer, or perhaps a doctor in scrubs. But in times past, for the 97% of people who made up the “laboring classes,” everyone knew what you did based either upon the clothes you wore or the afflictions from which you suffered—or both.

Jack London’s 1903 book The People of the Abyss is a first-hand account of what life was like in the working class slum known as the East End, in London. He bought the clothes of an unemployed American sailor at a second-hand clothing shop. He then spent several months living in workhouses, slums, and hop picking. It’s a fascinating (albeit wrenching) book.

In his book Endangered Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain, Anthony S. Wohl discusses a number of “industrial diseases” as having been accepted as an inevitable part of working life. Miners had asthma. Matchmakers had phossy jaw. Lead workers had palsy. You recognized the tailors by their concave chests and stooped shoulders, the potters by their paralyzed wrists, the copper workers by the greenish tint of their hair, teeth, and skin, and the hatters by their unsteady gait and trembling hands. (264-5)

It’s a different time, now, of course, and mass-production of clothing makes it much more difficult to tell who does what for a living. Still, whenever I’m in a big city, I enjoy trying to guess.

Anthony S. Wohl, Endangered Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983. All images except top one LOC.

![By Richwales (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-4.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sarahalbeebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Ballet_feet_2nd_position-1-450x233.png)