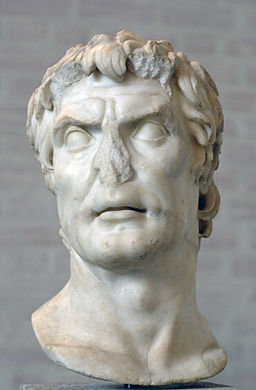

Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Roman Dictator

Bibi Saint-Pol, own work

The first time I stumbled across a reference to the disease known as phthiriasis (pronounced “thuh-RY-uh-sis) I was reading Plutarch’s gleeful account of the death of the Roman tyrant Sulla.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138 – 78 BC), who had a nasty habit of putting his enemies’ heads on pikes, died a relatively old man, having murdered all the people who might try to assassinate him. And yet, according to Plutarch, Sulla met a ghastly end.

Sulla became sick with an intestinal hemorrhage. Said Plutarch, “the corrupted flesh broke out into lice. Many men were employed day and night in destroying them, but they so multiplied that not only his clothes, baths, and basins, but his very food was polluted with them.”

According to this article by J. Bondeson MD, PhD, in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Sulla may or may not have had phthiriasis. If he did, the bugs swarming out of his guts were not lice but mites, which can infest a person with an already-weakened immune system. As Sulla was so roundly hated by most Romans, Plutarch may have simply wished he’d had the disease. That seems to have been a pattern: most ancient writers agreed that phthiriasis was a disease contracted as a punishment by the gods, divine retribution for tyrants and various enemies of prevailing religions.

J. Bondeson tells us that phthiriasis has a long history. Aristotle wrote about it. Galen did, too. So did Pliny the Elder, but he wasn’t much of a detail-oriented guy and was wrong about, well, pretty much everything. Still, there are lots of accounts of this gruesome flesh-eating disease from ancient times.

In Acts of the Apostles, after Herod Agrippa was hailed as a God, “an angel of the Lord smote him because he did not give God the glory, and he was eaten by worms and died.’

Doubt has been cast about whether this disease actually existed, but Bondeson cites several reliable cases of phthiriasis dating from the 16th century, and regular mention of it in textbooks and case reports well into the nineteenth century. In case after case, the victims fell ill with many swellings all over the body that eventually burst, and from which small insects streamed out. Nice. Linnaeus called it “louse fever,” and recommended slathering the patient with mercurial ointment.

Did the disease really exist? Bondeson and others believe so. He cites various entomologists who think the mites may have been a species similar to one that infests birds.

It remains a mystery as to why the disease vanished so suddenly by the 1870s. Some medical historians speculate that that species of mite may have gone extinct. Whatever happened to them, I’m glad they’re gone.